This paper was originally written for one of my history classes and I hope you enjoy the topic. Author’s update: After consideration, I have chosen to remove the citations from this paper for this post to prevent the misuse of the paper. I am more than happy to provide interested scholars with a copy.

In 1791, the Miami Indians of Ohio handed the United States its worst military defeat ever. Three years later, the Indians would learn the hard way about revenge. These two events, Gen. Arthur St. Clair’s defeat in 1791 and Gen. Anthony Wayne’s resounding victory at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794, raise many questions. What made these two battles have such different outcomes? What evidence exists from accounts of travelers years later? What can Americans learn from these events today? Both St. Clair’s defeat and the Battle of Fallen Timbers illustrate much about the early republic, how harsh lessons of warfare are taught through defeat, and that these lessons, when their mistakes are corrected lead to resounding success. The two events present an interesting story about the early history of our nation as well as relations with Native Americans at that time.

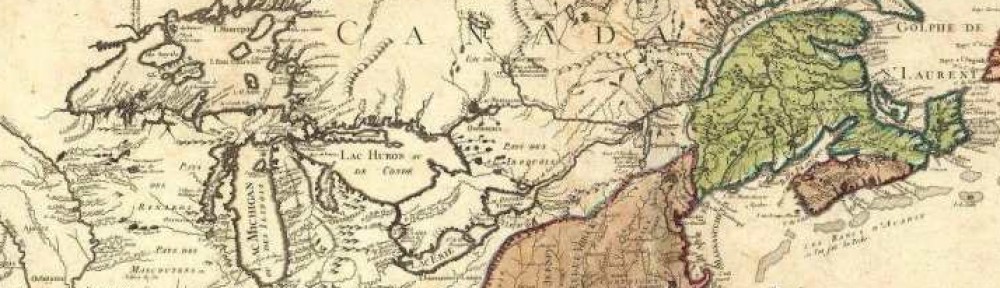

The frontier of the new United States was a wild and dangerous place in the late 18th century. New settlers to the Northwest Territory faced the prospect of Indian raids and the still present British forces stirring up the Indians and threatening war. Unfortunately, for Washington, settlers killing of peaceful Indians and raiding of Indian villages undermined the effort of conciliation by Washington’s administration and led to its failure. The United States faced challenges to their authority in the Old Northwest from persons like Joseph Brant, who encouraged fellow Indians to rise up and retake their lands. At this time, American governmental policy was to settle issues arising in the old Northwest with the Indians peacefully. George Washington and Henry Knox attempted to achieve peace through purchasing Indian land as opposed to conquering it through bloodshed. It was in this environment that Arthur St. Clair led his army to defeat while serving as the territorial governor. Estwick Evans, a traveler in the region in 1818, noted the site where the battle took place. He stated, “On the river Calumet, which enters the Wabash, stands fort Recovery, and just above this fort is the place of St. Clair’s defeat.” This account illustrates that this battle was so significant that even people years later noted it.

Leading up to the battle the frontier was in turmoil. Raiding expeditions by Indians were growing in frequency and a scout of St. Clair’s reported that many Indians in the region possessed “bad hearts.” As a result, Washington sent an expedition in 1790 under the command of Josiah Harmar to deal with the Indians, which consisted of poorly trained militia and others. Harmar met defeat, suffering around two hundred casualties. This defeat led to Washington authorizing the expedition led by St. Clair the next year. Things did not proceed well for St. Clair prior to the battle. Recruiting the army for the expedition was difficult and St. Clair described the army as being “collected from the streets . . . [as well as] from the stews and brothels of the cities.” Furthermore, many officers in the army had marginal experience fighting Indians. These issues ultimately led to the disastrous battle between St. Clair and the Indians.

What happened at the site described above by Evans was an event of unspeakable slaughter and horror. On November 4, 1791, Maj. Gen. St. Clair, having hoped “to establish a fort at the head of the Maumee River” became engaged near the Miami village named Kekionga against the Miami chief Little Turtle. Little Turtle, whose tribal name was Michikinikwa was one of the most respected and powerful chiefs in the region, which made him a formidable opponent for St. Clair’s force of around 1,400. Capt. Thomas Morris illustrated the power of the Miami in his account of the battle. Morris described the Miami as “the very people who have lately defeated the Americans in three different battles”. Shortly before daybreak, an Indian force of 1,040 warriors, composed of Shawnee, Miami, Delaware, as well as Ottawa, Chippewa, and various other tribes, encircled the American camp. The battle began when the Indians attacked the camp of a group of Kentucky militia approximately 270 strong, with a force of around 300. The Kentuckians fled in all directions and their pursuers eventually caught many of them. One of the militia, a man named Bradshaw, later recalled that upon being able to shake his pursuer, tripped him, and “drove [his] hunting knife through his throat, severing his jugular [vein]”. Another soldier described how a Captain Smith’s head smoked after he was scalped. The panicky militia left St. Clair’s army in a weakened state as the Indians attacked.

The main body of the American force, which consisted of much of the U.S. army as well as many camp followers, took positions in their rectangular encampment area of about 400 by 75 yards, which is why the militia was encamped in a separate area. With the militia in a retreat, St. Clair’s force now faced the full brunt of Little Turtle’s force. Thomas Irwin, a survivor of the battle later wrote that St. Clair and his other officers believed that the Indians “would not attack an army where there was so many [cannon] with them”. As the morning continued, St. Clair would begin to find out just how wrong his assumption was. Unfortunately, for St. Clair, his artillery was ineffective and made no dent in the Indian onslaught. The battle that ensued around St. Clair was one of the three that Capt. Morris referred to in his journal.

The battle began to wear away at St. Clair as he realized that the Indians were destroying his army. He ordered Col. William Oldham to lead a counter-attack similar to that of the Indians. Oldham reportedly told his commanding officer, “No, damn it, that’s suicide. I won’t do it”. St. Clair, shocked at this act of insubordination, responded to Oldham saying, “You’ll do it, Colonel, or by Christ I will run you through”. Right after this exchange, a ball tore off the back of Oldham’s skull and he fell forward dead in front of a stone-faced St. Clair. St. Clair attempted to rally his men, raising his sword and leading Oldham’s men in a bayonet charge against the enemy’s left flank. He repulsed the Indians briefly, however his men dropped so quickly that after three attempts too few men were available to mount a fourth charge. The troops discarded their equipment and fled to Fort Jefferson almost thirty miles south, which saved the army from suffering a “frontier Cannae.” The traveler Francois André Michaux later mentioned an officer who fell in the battle, Maj. Gen. Hart. He stated that, “This officer, of the most distinguished merit, fell in the famous battle that General St. Clair lost in 1791, near Lake [Erie], against the united savages”.

The result of Little Turtle’s attack was frightful. According to the above account, “The battle raged for three hours with the carnage among the Americans about twenty times that among the Indians”. The cost to the Americans:

. . . totaled 914, including 630 dead and 184 wounded. In addition, almost half of the estimated 200 camp followers, made up of wives, children, and prostitutes, were killed. Fewer than 500 of the 1,400 soldiers escaped with a whole skin.

Clearly, Little Turtle had handed the Americans not only a horrible strategic defeat, but a psychological one as well. Of the American dead, 37 were officers, compared to an estimated 151 Indians killed. How Little Turtle’s forces defeated the Americans so soundly lies in their style of fighting as well as some interesting allies.

The Indians enjoyed a system of organization that would be advantageous to them as they fell upon the Americans. The Indians had put aside all of their differences and formed a tribal alliance, in which all tribes were enthusiastic in their roles in defeating the whites. One of the successes in this alliance was the presence of an overall leader in Little Turtle. In addition to Little Turtle, the warrior Tecumseh played a role prior to the battle as a scout, though he did not take part in the actual battle. In addition to Tecumseh, Little Turtle also had a white man on his side at the battle. William Wells, Little Turtle’s son-in-law, was captured years earlier at age 13 and had since fought alongside his adopted people with bravery. Wells also played a role at Fallen Timbers, which will be discussed later.

Another advantage that Little Turtle’s force possessed was in tactics. According to an account from the battle, the Indians “concentrated their shots on the active officers whom they could easily distinguish”. The account continued, mentioning that “General St. Clair had six bullet holes in his clothing but was not wounded.”, however “General Butler was killed”. The Indians were able to use advantages that favored them and would ultimately win the day. However, this incredible victory would be short lived, as the Indians would eventually face a revitalized American army under a new, tougher commander, “Mad” Anthony Wayne.

After the disastrous defeat of St. Clair’s army, the United States faced the threat of Indians with a much smaller army since many had been killed or wounded in the battle. The defeat spread panic across the frontier as far away as Pittsburgh, but fortunately, for the United States, the Indians did not follow-up on their victory. One of the consequences for the young republic that resulted from this defeat was the first Congressional investigation under the federal Constitution. St. Clair wished to resign his commission and retire while keeping his generalship. However, President Washington decided not to allow this. The investigating committee did not directly criticize St. Clair; however, they found one key area that may have contributed to the defeat. The committee noted,

. . . that the 2,300 men gathered at Fort Washington were reduced to 1,700 “fit for duty” by the time the army began the last leg of its journey on October 24; and that their numbers were further reduced to 1,400 on October 31 when “about sixty of the Kentucky militia deserted in a body and the first regiment [of regulars] was detached with a view to cover a convoy of provision . . .

In the end, St. Clair resigned his commission on April 7, 1792 and Anthony Wayne, a veteran of the Revolutionary War, took command. The stage was set for Wayne to enact revenge on the Indians.

Wayne, an experienced Indian fighter, drove the ideas of “tactics, training, and discipline” into his new “Legion of the United States”. The Legion consisted of four “sub-legions”, which consisted of two battalions of infantry, one battalion of riflemen, a troop of dragoons (cavalry that fought both mounted and dismounted), and an artillery company. This organization placed the combined arms under one command, with each sub-legion commanded by a brigadier general. By the autumn of 1793, Wayne was ready and pushed northward. However, a lack of supplies forced Wayne to halt his push and his army encamped at Greenville, where he continued to train his men. By the summer of 1794, Wayne’s army was ready to move. In addition to the training, Wayne gained an important ally. William Wells, the adopted white son-in-law of Little Turtle was negotiating on behalf of the Indians in 1792 at Vincennes. While at the meeting, Wells reunited with his brother, who convinced Wells to return to Kentucky where Wells joined the army as a scout. Wayne was ready for a fight, and having made no contact with the enemy on the eve of the battle, he set his men to the task of constructing a camp, which they named Camp Deposit. Little Turtle was confident that he could defeat Wayne and make him “walk in a bloody path”. Little Turtle had every reason to be confident, having defeated St. Clair’s poorly trained army three years earlier; however, Wayne was not St. Clair and Little Turtle would learn that the hard way.

The “confederated” Indian tribes moved into position on August 18, having fasted in order to make stomach wounds less severe. However, they did not meet the enemy, soon grew weak from hunger and thirst, and dwindled in numbers until only around 500 remained to meet 1,000 Americans. In addition, a sever thunderstorm on August 19 forced many Indians to leave the area to seek shelter at their camp near Fort Miami, a British fort. Among those who remained were Tecumseh and his Shawnee warriors. According to the journal of William Clark, of future Lewis and Clark fame, the battle on August 20 began with, “a [shower] of Rain [which] prevented our move at the [hour] appointed”. Clark further noted that by seven that morning the army had formed “Line of March” and was experiencing difficulties as they faced thick woods on their left and “a number of [steep ravines]” on the right. Clark added that after two hours that the advance guard of the army spotted the enemy and took fire. It was Tecumseh and his fellow Shawnee who ambushed the advance guard, but soon fell back as they realized that the advance guard was part of a much different, better-disciplined army. The battle that would go down in history as the Battle of Fallen Timbers had begun.

After the initial encounter with the Indians, the advance guard retreated to the main body of the army. The right flank of the army, led by Gen. Wilkinson, upon taking enemy fire, immediately “formed [and] returned fire”. A combined infantry and mounted charge, in which Capt. Campbell, the leader of the mounted troops was killed, forced the Indians to quit the field. The Indians attempted to attack the left flank, but were repulsed. A cavalry charge drove the enemy back about three-quarters of a mile, and the army replenished itself with whiskey, pushed the enemy from the field, and then advanced to within one mile of a British garrison. Having accomplished this, the army then made camp near the British garrison.

Wayne’s resounding victory did not come without a price. What Gen. Wilkinson described as “a mere skirmish” cost the Legion 133 men, of these 33 were dead including two officers. According to the journal of Clark, the two officers were Capt. Campbell and Lt. Towles, and the number of American dead was 240, compared to 30 to 40 enemy dead out of a force of 900 Indians and 150 Canadians. Clark’s figures may be in dispute, due to different figures appearing in other sources. However, Clark was at the battle, but the problems with Clark’s figures are that they appear to make the victory hollow due to difference in number of lives lost on both sides. One thing that remains constant is that Wayne had achieved an incredible victory over the Indians.

In the aftermath of the victory, the Indians were in a panic. The British commander noted with disgust that the Indians “behaved excessive ill . . . and afterwards fled in every direction”. He further added that “their panic was so great that the appearance of fifty Americans would have totally routed them” Another British officer, Lt. Col. England, noted, “that the confederated tribes no longer could be relied on for the primary defense of the Detroit region”. These observations illustrate the magnitude of Wayne’s victory.

For days after the battle, Wayne remained near the British outpost, Fort Miami. They burned villages and crops of their recently defeated foes. This was in an effort to draw the British force at Fort Miami out to fight. Wayne realized that the British commander, Major Campbell, intended to hold the post and remain inside in defiance of Wayne’s blustering and displaying his army in front of the fort. Wayne did not want the blame for starting a war between the U.S. and Britain, and, realizing that his tactics did not affect the British, soon withdrew his army to focus on destroying the Indian resistance.

Travelers to the region years later noted both battles and even met with people who served at Fallen Timbers and fortunately, their experiences remain. George W. Ogden passed through the areas of Greenville and Fort Recovery, and noted, “just above this fort is the memorable place of St. Clair’s defeat”. Francois André Michaux noted that the army marched against the Indians in defense of settlers and that the repulsion of the Indians, culminated in Wayne’s victory at Fallen Timbers. Estwick Evans mentioned a meeting with a Col. P. who was “an officer under General Wayne, during his famous expedition against the [Indians]”. Tilly Buttrick traveled in the lower Sandusky, which was known to be “an important Wyandot village” prior to Fallen Timbers. Buttrick pressed on to Greenville, where Wayne built a fort and established his headquarters after the battle. Edward Flagg mentioned having met with a pioneer who had hunted “where Boone, and Whitley, and Kenton once roved”. The man named Kenton that Flagg refers to is Simon Kenton who served with the army during Wayne’s campaign. These travelers knew of the events surrounding the places they visited and met with many people along the way who had taken part in them, thus making the stories of their travels more interesting and valuable to historians today.

While St. Clair forced a congressional investigation, Wayne forced a peace. Having defeated the Indians and establishing his base at Greenville, in 1795, Wayne prepared to make peace with the Indians. Major Thomas Hunt, commander of Fort Defiance, reported to Wayne the conditions of the Indians. He stated that, “The poor devils were almost starving to death before they got here”. Timothy Pickering, the negotiator, wanted the treaty to hand over more territory to the United States. Wayne was allocated $25,000 in various goods, which included hats, blankets, knives, axes, wine, and liquor. On July 15, 1795, Wayne began the council, stating, “Younger brothers, . . . I take you all by the hand” and “Rest assured of a sincere welcome . . . from your friend and brother Anthony Wayne”. Using the Treaty of Paris (1783) and the Fort Harmar Treaty, Wayne justified the Americans right to the Indian lands. While Little Turtle argued that the Americans were taking the best Indian lands, many chiefs accepted the treaty and the council closed on August 10 with Little Turtle swearing allegiance to the United States on August 12. With the signing of the Treaty of Greenville, the war between the United States and the Northwest Indians was over.

St. Clair’s defeat and the Battle of Fallen Timbers illustrate both the weakness of and strength of the new republic. St. Clair’s bungled campaign led to the worst military defeat at the hands of the Indians for the army. Even though he should have been able to use his superior numbers to crush the Indians, his cockiness and coldness would be his downfall. On the other hand, Little Turtle, fresh from this victory would view the American army with contempt and thus would meet his own defeat at the hands of a much more experienced Indian fighter and general, Anthony Wayne. These two events shaped the history of the new nation, with St. Clair’s defeat bringing about the first congressional investigation in the history of the constitutional system. Wayne’s victory would eventually allow for the creation of a new state, Ohio and ensured that the United States controlled the northwest. Travelers observed these events in their accounts years later, illustrating the impact that these battles had on history. The mistakes St. Clair made led to the United States reexamining its strategy against the Indians. Wayne learned from St. Clair’s undisciplined army by instilling strong discipline in his Legion. He also utilized his army better than St. Clair, with his troops regrouping and returning fire instead of breaking as St. Clair’s army did. In addition, Wayne waited until his enemy was weak in contrast to St. Clair’s cockiness, which caused St. Clair to be surprised. In contrast, Little Turtle and his forces did not learn from their victory and underestimated the resolve of their enemy, which would lead to their defeat and loss of their land. These two events are important illustrations for both early American history and the history of Native Americans as well.

Pingback: ann bancroft and liv arnesen

Hello,

I am a scholar from Warsaw Univeristy. My Ph.d thesis focuses on American Indian Policy in the XIX century. Currently I am working the part concerning gen. Wayne’s campaign. Apart from some primary sources I have in my posession ( american state papers, journal of wayne’s campaign, william clark’s journal of the campaign, etc) I am looking for some other sources, like:

1. Boyer, John

“Daily Journal of Wayne’s Campaign, from July 28th to November 2d, 1794, including an account of the memorable battle of 20th August.” American Pioneer I (315-22, 351-57).

2. Draper, Lyman C.

1842 “Reminiscences of Gen. Brady on Wayne’s Campaign, Detroit, August 13, 1842” Draper Mss 5U 126-150 Wisconsin Historical Society.

[Lt. Brady, Preston’s Rifle Company, 4th Sublegion]

1842 “Jerimiah Armstrong Narrative Col. Aug 3d 1842” Draper Mss 5u 151-159 Wisconsin Historical Society.

3. Knopf, Richard C.

1953 “Two Journals of the Kentucky Volunteers 1793 and 1794” The Filson Club History Quarterly 27 (247-81)

4.Smith, Dwight L. (ed.)

1952 From Greene Ville to Fallen Timbers: A journal of the Wayne Campaign July 28-September 14, 1794. Indiana Historical Society, Indianapolis.

[Anonymous Journal – Probably Gen. James Wilkinson or his aide]

5.Wilson, Frazer E.

1935 Journal of Capt. Daniel Bradley: An Epic of the Ohio Frontier Frank H. Jobes & Son, Greeneville, Ohio.

[Officer in 2nd(?) Sublegion]

Maybe you could help me in any way? I would be very much grateful.

best regards,

Michal

Michal,

First, best of luck with your Ph.D. I am surprised that Warsaw University has a program that offers the training to work on such a topic. As to your question for help locating sources, I do not personally have any of these in my possession, but what I can suggest is that you see if they have been digitized either through Google Books or http://www.arhcive.org (would be under American Libraries). If these do not pan out, then your next option is to use World Cat and find libraries that have them and see what their policies are regarding copying the material and shipping it to you. It may be expensive, but those works would be very useful to you. I hope this helps you. Again best of luck.

Daniel

Dear Sauerwein;

Thank you for your informative article on General St. Clair’s engagement. I have some suggestions of some other lessons learned. With very close scrutiny and about 30 years study of American horse-and-musket era military history I have some thoughts upon comparing the two battles.

The surprise of the command seems to have allowed the Native force to enter the main camp pell mell with the fleeing militia. The Indians were apparently forced out of the camp but were able to fire upon our troops in ranks from cover. By lying down under cover they could fire from a rest quite effectively. It appears to me that there were a few attempts to drive these hidden foes from the front by an advance with the bayonet. These attempts were limited to single battalions with small fronts. Any such advance would clear the immediate front of that unit as the Indians would readily retreat. But the flanks of the line would be open to deadly enfilade fire from warriors not in their front. Upon realization of this demoralizing situation the American line would retire to its original position while the Indians that had retreated simply advance again retaking their ground and firing with increased confidence and even more deadly aim at the backs of the infantrymen. Once attacked it was well nigh impossible to defend an unfortified position with the bayonet alone against a highly mobile force utilizing firearms.

General Wayne’s tactics successfully utilized the bayonet as THE primary weapon because the Legion was not forced to hold ground. They moved forward steadily while the Native force fired their weapons but apparently had no time to reload. They had no choice but to retire from the field as they could not successfully close for hand-to-hand combat with a line of men armed with bayonets. A tomahawk or knife (or even a sword) was no match for a well handled line of bayonets.

Thank you for your article, I found it very interesting and thank you for helping to keep this period of our history in our collective memory.

Yours quite cordially and most respectfully,

Chuck Brown

I understand the United States Army is studying ‘Panic’ as part of its non lethal weapons program. Something about the Army hired several Hollywood movie producers to work on the project. The goal of the project was to induce, through artifical means, such ‘gripping fear’ that the enemy would break and run.

I can recall little of the paper but I remember it mentioning two events. One was the initial engagement of the Iraqi forces in Desert Storm (1991) where the American Army sent Bradleys (APCs) to lay down protected fire as M60A2 tanks with bulldozers buried Iraqi soldiers alive in their trench positions. Iraqi soldiers who witnessed the assult ‘simply freaked’ and ran away (much like Ypers 1915)

The other battle mentioned was the Battle of Little Big Horn (1876) where troops of COL Custer were so terror-stricken that several members of the initial skirmish line put their cartridges in backwards (Evidence at the battlefield revealed cartridges with strikes to their bullets as opposed to cartridge rims.

I’ve known about St. Clair’s defeat (overview) for some time but most people know little about it (or the Fetterman Massacre of 1866). St. Clair’s defeat was the greatest defeat George Washington ever experienced (as CNC, the buck stops with GEN Washington).

I am suprised no one ever made a movie about it because it would be unbelievable, even by Twenty-First Century Hollywood ‘political correctness’ standards.

1. United Tribes under Little Turtle, magnificantly captained by Wells, an adopted white boy turned learned warrior.

2. Pitted against half of the American Army who GEN St. Clair described as ‘the Creme de la Creme of America’s streets, soup kitchens and bordellos’

3. That one sixth of the engaged American Fighting force consisted of camp followers (women, children, washer-women and prostitutes)

4. That after the militia had broken, women and children of the camp followers joined the ranks of the Regular Army to battle the Indians

5. That over a thousand US troops had been killed, most being UNARMED and simply hunted down like frightened animals.

6. That Indian losses were less than one sixth of American Losses and

7. That the Indians roasted so many Americans (put them on sticks) alive that their screams could be heard up to three days after the battle.

8. That the ensuing debacle not only caused America’s first cabinet but the first envoking of EXECUTIVE PRIVLEDGE

I am interested in the terror aspect of the battle, specifically: 1. What caused the Psychological breakdown to cause American troops to abandon their weapons and bolt 2. The wound to the cultural Psyke (concerning the savagery of Indian warriors). Indeed, the trama of this event (St. Clair’s defeat and being hunted down/roasted alive) was so deep that it was one of the causitive factors which caused Brigideer General Hull to surrender his command (ten times the fighting force) to the British without firing a single shot in anger. CPTG

With due respect, I don’t know where that idea about cartridges being put in backward ever came from but, as I remember, most of Custer’s men had “trapdoor” Springfields and those used a rimmed (but center fire) cartridge. Perhaps it is another weapon they’re talking about though, like a Colt SA Army.

Very interesting thread though.

One of my ancestors was the Captain of the Rangers for Gen. Wayne and I’ve always been curious if he was with St.Clair. Does anyone know of a roster or such?

Thanks,

Perk (:>)

A very intresting read. As a native Ohioan, I am intrigued by this period in our history. In his epic historical novel The Frontiersmen, Alan W. Eckert gives a very harowwing account of St. Clair,s defeat. When Anthony Wayne returned the following year, to build Fort Recovery, one of the first tasks his men had, was the gruesome detail of gathering the hundreds of skulls and bones of the slaughter of 1791, which according to one account, made the gound where they lay, white. If you visit the site today, there is a 90.ft obelisk, where the remains are at rest. Inscribed on the obelisk are the names of all the officers who died in the battle. To the south, is a full scale reproduction of the fort, with many genuine relics from the site.

Excellent.

Excellent web site you have got here.. It’s hard to find quality writing like yours nowadays. I honestly appreciate people like you! Take care!!

Little Turtle did not lead the strike against Wayne, that was Blue Jacket. Little Turtle did fight, but he wanted peace. The other Native American tribes did not agree with that so they removed him and put him in charge of his 200 Miami brethren. They replaced him with Blue Jacket and possibly someone else (I forgot the name). He did fought, but he wanted peace. Little Turtle led the strike in the other battles before this. After this, he was very peaceful, and even met with George Washington. Little Turtle received a house on a river and tried to convert his people into peaceful farmers. Tecumseh even tried to get Little Turtle to join the resistance years later, but he refused. Blue Jacket led the Native Americans in the Battle of Fallen Timbers and learned from the lost of his land. Not Little Turtle. I got all of this information from Chronicle of the Indian Wars by Alan Axelrod and other sources.

Ashley,

I just stumbled upon your comment and want to thank you for it. While you are correct that Blue Jacket was the combat commander for the Native force at Fallen Timbers, Little Turtle still retained overall control over the Miami, hence why he was referenced, though I must admit that I should have clarified this point. Your mention of Blue Jacket is important, as he also assisted Little Turtle in commanding the forces at St. Clair’s Defeat. Your mention of Axelrod’s book is interesting, as his work is a more generalized reference on Native American warfare covering a broad spectrum of time. I’m curious to know the other sources you consulted, as I can tell you that the post is from a paper I wrote in graduate school based on a number of solid works on both battles. Again, thank you for your comment and have a wonderful day.

Daniel