I wrote the following review for On Point: The Journal of Army History and it will appear in an upcoming issue.

I wrote the following review for On Point: The Journal of Army History and it will appear in an upcoming issue.

The First Way of War: American War Making on the Frontier, 1607-1814. By John Grenier. Cambridge University Press, 2005. i-xiv, 232 Pp. Figures. Maps. Index. ISBN 0-521-84566-1. $30.00

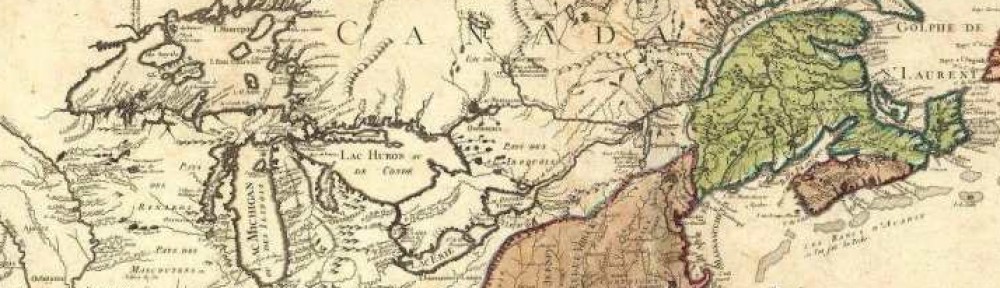

Through gripping accounts taken from primary sources to maps of the regions in question, Air Force officer and Air Force Academy history Professor John Grenier argues and illustrates how America developed its unique military heritage and style of war making based upon irregular warfare. Specifically, Grenier examines the killing of non-combatants and destruction of crops and homes during the wars in the colonies as well as the American Revolution, the Indian wars of the early republic, and the War of 1812.

In his introduction, Grenier discusses the history and historiography of military and specifically American military history, including the development of America’s unique way of making war. He lists off several historians and works from the past that discuss this topic, which provide the reader with a good background on the subject presented in this work.

Grenier presents the history of American rangers through much of the work and he keeps the story in chronological order beginning with the wars in the colonies from 1607-1689, which occurred between colonists and Indian tribes. He brings to light how ranger companies were generational with sons often leading units that their fathers once led. He then moves into the wars on the continent between France and England in the eighteenth century as well as the lesser-known wars, noting the role that rangers and the tactics they used played in the conflicts in the mid-eighteenth century prior to the French and Indian War (1754-1763).

Grenier then breaks the flow of the work with a chapter dealing with the history of petite guerre in Europe. This story is important for understanding this work, but would better serve the work if it was the first chapter as in the current placement as the third chapter, it breaks the flow in a way that hurts the story that the author is presenting. This is not to say that the chapter does not belong as it does, but rather that it belongs in a different place within the larger work.

Grenier then examines America’s way of war making in the French and Indian War. He notes that Britain realizes the need for American rangers, especially after Braddock’s defeat, but that they are slow to realize this. Shortly after Braddock’s defeat, various units of American rangers are formed in response, including one unit formed by Robert Rogers (the famous Roger’s Rangers). He also notes how the British after initially relying on the rangers attempt to replace them, but fail. Finally, he concludes the chapter by examining how the British adapt the American way of war.

Grenier also examines the Revolutionary War period, primarily focusing on the war on the frontier, which includes stories about George Rogers Clark as well as the Northeast frontier. Grenier then examines the 1790s, which present great defeats and triumphs on the frontier from St. Clair’s defeat to the Battle of Fallen Timbers. The story then carries into the early 1800s, focusing on events like the Indian war in the Northwest against Tecumseh and the Creek War to the south, finally ending in 1815.

Overall, Grenier’s scholarship is quite good with many primary sources drawn together for this work, including the papers of Sir William Johnson, as well as many government documents. He also provides a good selection of maps and illustrations to aid the reader in understanding. His style is formal, but not beyond the general reading audience, which gives it a wider audience as both historians and general readers can understand the book. Though he is an Air Force officer, Grenier proves that he knows the subject well. His work adds greatly to the scholarship of both American history and US Army history. Both historians interested in the topic and general audiences will benefit from reading The First Way of War.

When Professor Russell Weigley concentrated his monumental study on large recognizable military formations his work focused on those conventional formations that operated along established rules of war. John Grenier attempts to demonstrate that along the American colonial frontier such conduct gave way to an unprecedented organized violence, that for the first time on the new continent, distinguished neither combatant nor non-combatant. This “first way of war” according to Grenier “accepted, legitimized, and encouraged attacks upon and the destruction of noncombatants, villages, and agricultural resources . . . in shocking violent campaigns to achieve their goals of conquest.” Tracing the advent of such violence to the initial decades of English colonization, Grenier opines that colonial military leaders resorted to tactics learned in the brutal wars of religion. Thus, civilian and military authorities unleashed an “extirpative war” against normally peaceful tribesmen which sought their complete destruction in a total war like atmosphere not seen since the Thirty Years War in Germany. Grenier posits that the American adoption of petit guerre begins an important ranger tradition which, according to Grenier, leads to more sinister ways of war such as colonial authorized scalp bounties and scalp hunting, and war making on native non-combatants which become the bedrock of an accepted “first way of war.” Grenier does thoroughly quantify the escalating levels of violence that typified frontier European and Indian warfare. His recounting of the strategic evolution in the colonial use of ranger companies in response to an illusive deadly Neolithic forest foe appears more typical of the uniquely American military innovational response to an operational necessity rather than establishing a precedent of “extirpative war.”

While Weigely’s work noted the beginnings, in the seventeenth century, of the brutal nature of a total war, in response to like Indian attacks on the frontier, he did not affix claims of aggressive responsibility in the way that Grenier’s study does to European settlers. Such claims are unfortunate and appear to pander to current themes of academic political correctness rather than factual historical interpretation. While concentrating on European excesses in response to atrocities perpetrated by their Indian and often French allies, Grenier passes on an opportunity to objectively consider the motivations and anthropological connections regarding intercine Indian brutality. There is no question that what the early European whites considered “atrocities” perpetrated on them may have actually been no more than long accepted and established tribal customs of the “warrior culture” of these neo- Neolithic peoples. Thus, the brutal ethos of the frontier left a heavily documented imprint on the earliest settlers. Contrary to Grenier’s claim that such slaughters were a consequence of contact with modern Europeans, archaeology yields evidence of prehistoric massacres more severe than any recounted in ethnography. For example in Keeley’s “War Before Civilization,” a study ignored by Grenier, archaeologists have found several mass graves, one, at Crow Creek, South Dakota, which contained the remains of more than 500 men, women and children slaughtered, scalped and mutilated in an attack on their village a century and a half before Columbus’s arrival. What archaeology reveals from this period is that a member of a typical tribal society, especially a male, had a far higher probability of “dying by the sword” than a citizen of the average modern state. Our civilization allows us to conceive and establish social structures which will never lead us away from the use of weapons and defenses; however nostalgia for an imaginary tranquil peace of the primitives and Amerind non-state societies does not contribute factually to the discussion of European-Amerind contact. Unfortunately, The First Way of War: American War Making on the Frontier demonstrates that the myth of the peace-loving “noble savage” is as persistent as it is pernicious.