Most Americans believe that the Declaration of Independence by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776 began American independence. While this date announced the formal break between the American colonists and the “mother country,” it did not guarantee independence. Not all Americans favored independence and most historical estimates place the number of Loyalist, or Tory, Americans near one-third of the population. Winning independence required an eight-year war that began in April, 1775 and ended with a peace treaty finalized on September 3, 1783. Unfortunately the infant nation found itself born in a world dominated by a superpower struggle between England and France. The more powerful European nations viewed the vulnerable United States, correctly, as weak and ripe for exploitation. Tragically, few Americans know of this period of crisis in our nation’s history because of the irresponsible neglect of the American education system.

American independence marked the end of one chapter in American history and the beginning of another. As with all historical events this declaration continued the endless cycle of action and reaction, because nothing occurs in a vacuum. Tragically, most Americans’ historical perspective begins with their birth, rendering everything that previously occurred irrelevant. Furthermore, most educators conveniently “compartmentalize” their subjects and do not place them in the proper historical context. Since most Americans only remember the United States as a superpower they do not know of our previous struggles. Unfortunately our agenda driven education system also ignores this period and often portrays America in the most negative light.

Without delving too deeply into the deteriorating relations between the American colonists and their “mother country,” declaring independence came slowly. None of the thirteen colonies trusted the other colonies and rarely acted in concert, even during times of crisis. Regional and cultural differences between New England, mid-Atlantic and the Southern colonies deeply divided the colonists. Even in these early days of America slavery proved a dividing issue, although few believed in racial equality. The “umbilical cord” with England provided the only unifying constant that bound them together culturally and politically.

The colonies further possessed different forms of government as well, although they steadfastly expressed their liberties and “rights as Englishmen.” Some colonies existed as royal colonies, where the English monarch selected the governor. Proprietary colonies formed when merchant companies or individuals, called proprietors, received a royal grant and appointed the governor. Charter colonies received their charters much as proprietary colonies with individuals or merchants receiving royal charters and shareholders selected the governor. Each colony elected its own legislature and local communities made their laws mostly based on English common law. Any form of national, or “continental,” unity remained an illusion largely in the minds of the delegates of the First Continental Congress.

The Second Continental Congress convened on May 10, 1775 because England ignored the grievances submitted by the First Continental Congress. Furthermore, open warfare erupted in Massachusetts between British troops and the colonial militia at Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775. Known today as Patriot’s Day few Americans outside of Massachusetts celebrate it, or even know of it. Setting forth their reasons for taking up arms against England, they established the Continental Army on June 14, 1775. For attempting a united front, they appointed George Washington, a Virginian, as commander-in-chief. On July 10, 1775, the Congress sent Parliament one last appeal for resolving their differences, which proved futile.

While Congress determined the political future of the colonies fighting continued around Boston, beginning with the bloody battle on Breed’s Hill on June 17, 1775. Known as the Battle of Bunker Hill in our history the British victory cost over 1,000 British and over 400 American casualties. This battle encouraged the Americans because it proved the “colonials” capable of standing against British regulars. British forces withdrew from Boston in March, 1776 and awaited reinforcements from England as fighting erupted in other colonies.

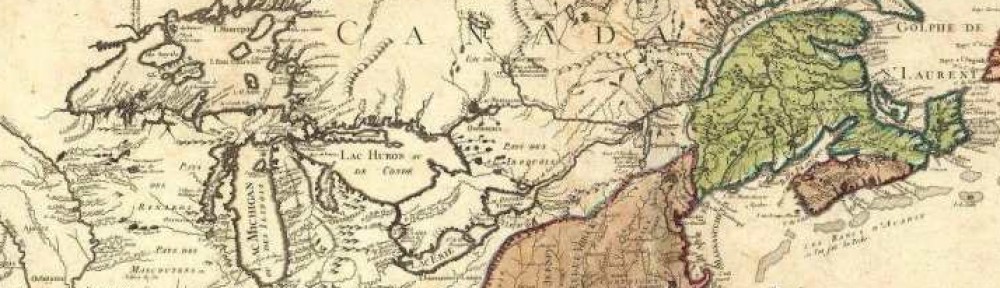

While Washington and the Continental Army watched the British in Boston, Congress authorized an expedition against Canada. They hoped for significant resentment of British rule by the majority of French inhabitants, something they misjudged. In September, 1775 the fledgling Continental Army launched an ambitious, but futile, two-pronged invasion of Canada. Launched late in the season, particularly for Canada, it nevertheless almost succeeded, capturing Montreal and moving on Quebec. It ended in a night attack in a snowstorm on December 31, 1775 when the commander fell dead and the second-in-command fell severely wounded. American forces did breach the city walls, however when the attack broke down these men became prisoners of war.

For disrupting the flow of British supplies into America Congress organized the Continental Navy and Continental Marines on October 13, 1775 and November 10, 1775, respectively. Still, no demands for independence despite the creation of national armed forces, the invasion of a “foreign country” and all the trappings of a national government.

The full title of the Declaration of Independence ends with “thirteen united States of America,” with united in lower case. I found no evidence that the Founding Fathers did this intentionally, or whether it merely reflected the writing style of the time. Despite everything mentioned previously regarding “continental” actions, the thirteen colonies jealously guarded their sovereignty.

Although Congress declared independence England did not acknowledge the legality of this resolution and considered the colonies “in rebellion.” England assembled land and naval forces of over 40,000, including German mercenaries, for subduing the “insurrection.” This timeless lesson proves the uselessness of passing resolutions with no credible threat of force backing them up. Unfortunately our academic-dominated society today believes merely the passage of laws and international resolutions forces compliance.

We hear much in the news today about “intelligence failures” regarding the war against terrorism. England definitely experienced an “intelligence failure” as it launched an expedition for “suppressing” this “insurrection” by a “few hotheads.” First, they under estimated the extent of dissatisfaction among the Americans, spurred into action by such “rabble rousers” as John Adams. They further under estimated the effectiveness of Washington and the Continental Army, particularly after the American victories at Trenton and Princeton.

British officials further under estimated the number of Loyalists with the enthusiasm for taking up arms for the British. While Loyalist units fought well, particularly in the South and the New York frontier, they depended heavily on the support of British regulars. Once British forces withdrew, particularly in the South, the Loyalist forces either followed them or disappeared. A perennial lesson for military planners today, do not worry about your “footprint,” decisively defeat your enemy. This hardens the resolve of your supporters, influences the “neutrals” in your favor and reduces the favorability of your enemies.

Regarding the “national defense” the Continental Congress and “states” did not fully cooperate against the superpower, England. The raising of the Continental Army fell on the individual colonies almost throughout the war with the Congress establishing quotas. Unfortunately, none of the colonies ever met their quota for Continental regiments, with the soldiers negotiating one-year enlistments.

Continental Army recruiters often met with competition from the individual colonies, who preferred fielding their militias. The Congress offered bounties in the almost worthless “Continental Currency” and service far from home in the Continental Army. Colonial governments offered higher bounties in local currencies, or British pounds, and part-time service near home.

Congress only possessed the authority for requesting troops and supplies from the colonial governors, who often did not comply. For most of the war the Continental Army remained under strength, poorly supplied, poorly armed and mostly unpaid. Volumes of history describe the harsh winters endured by the Continentals at Valley Forge and Morristown, New Jersey the following year.

Colonial governments often refused supplies for troops from other colonies, even though those troops fought inside their borders. As inflation continued devaluing “Continental Currency” farmers and merchants preferred trading with British agents, who often paid in gold. This created strong resentment from the soldiers who suffered the hardships of war and the civilians who profited from this trade. In fairness, the staggering cost of financing the war severely taxed the colonial governments and local economies, forcing hard choices.

Congress further declared independence as a cry for help from England’s superpower rival, France, and other nations jealous of England. Smarting from defeat in the Seven Years War (French and Indian War in America), and a significant reduction in its colonial empire, France burned for revenge. France’s ally, Spain, also suffered defeat and loss of territory during this war and sought advantage in the American war. However, France and Spain both needed American victories before they risked their troops and treasures. With vast colonial empires of their own they hesitated at supporting a colonial rebellion in America. As monarchies, France and Spain held no love of “republican ideals” or “liberties,” and mostly pursued independent strategies against England. Fortunately their focus at recouping their former possessions helped diminish the number of British forces facing the Americans.

On the political front the Congress knew that the new nation needed some form of national government for its survival. Unfortunately the Congress fell short on this issue, enacting the weak Articles of Confederation on November 15, 1777. Delegates so feared the “tyranny” of a strong central government, as well as they feared their neighbors, that they rejected national authority. In effect, the congressional delegates created thirteen independent nations instead of one, and our nation suffered from it. Amending this confederation required the approval of all thirteen states, virtually paralyzing any national effort. This form of government lasted until the adoption of the US Constitution on September 17, 1787.

Despite these weaknesses the fledgling “United States” survived and even achieved some success against British forces. Particularly early in the war, the British forces possessed several opportunities for destroying the Continental Army and ending the rebellion. Fortunately for us British commanders proved lethargic and complacent, believing the “colonial rabble” incapable of defeating them. Furthermore, as the Continental Army gained experience and training it grew more professional, standing toe-to-toe against the British. Since the US achieved superpower status it fell into the same trap, continuously underestimating less powerful enemies.

The surrender of British forces at Yorktown, Virginia on October 19, 1781 changed British policy regarding its American colonies. British forces now controlled mainly three enclaves: New York City; Charleston, South Carolina and Savannah, Georgia. Loyalist forces, discouraged by British reverses, either retreated into these enclaves, departed America or surrendered. Waging a global war against France and Spain further reduced the number of troops available for the American theater. This serves another modern lesson for maintaining adequate forces for meeting not only your superpower responsibilities, but executing unforeseen contingencies.

Ironically, the victory at Yorktown almost defeated the Americans as well, since the civil authorities almost stopped military recruitment. Washington struggled at maintaining significant forces for confronting the remaining British forces in their enclaves. An aggressive British commander may still score a strategic advantage by striking at demobilizing American forces. Fortunately, the British government lost heart for retaining America and announced the beginning of peace negotiations in August, 1782.

The Treaty of Paris, signed on September 3, 1783 officially ended the American Revolution; however it did not end America’s struggles. American negotiators proved somewhat naïve in these negotiations against their more experienced European counterparts. Of importance, the British believed American independence a short-lived situation, given the disunity among Americans. Congress began discharging the Continental Army before the formal signing of the treaty, leaving less than one hundred on duty.

Instead of a united “allied” front, America, France and Spain virtually negotiated separate treaties with England, delighting the British. They believed that by creating dissension among the wartime allies they furthered their position with their former colonies. If confronted with a new war with more powerful France and Spain, America might rejoin the British Empire.

When England formally established the western boundary of the US at the Mississippi River it did not consult its Indian allies. These tribes did not see themselves as “defeated nations,” since they often defeated the Americans. Spanish forces captured several British posts in this territory and therefore claimed a significant part of the southeastern US.

France, who practically bankrupted itself in financing the American cause and waging its own war against England, expected an American ally. Unfortunately, the US proved a liability and incapable of repaying France for the money loaned during the war. France soon faced domestic problems that resulted in the French Revolution in 1789.

For several reasons England believed itself the winner of these negotiations, and in a more favorable situation, globally. England controlled Canada, from where it closely monitored the unfolding events in the US, and sowed mischief. It illegally occupied several military forts on American territory and incited the Indian tribes against the American frontier. By default, England controlled all of the American territory north of the Ohio River and west of the Appalachian Mountains.

Economically, England still believed that the US needed them as its primary trading partner, whether independent or not. A strong pro-British faction in America called for closer economic ties with the former “mother country.” As England observed the chaos that gripped the US at this time, they felt that its collapse, and reconquest by England, only a matter of time.

Most Americans today, knowing only the economic, industrial and military power of America cannot fathom the turmoil of this time. The weak central government and all the states accumulated a huge war debt, leaving them financially unstable. While the US possessed rich natural resources it lacked the industrial capabilities for developing them, without foreign investment. With no military forces, the nation lacked the ability of defending its sovereignty and its citizens. From all appearances our infant nation seemed stillborn, or as the vulnerable prey for the more powerful Europeans.

As stated previously the Articles of Confederation actually created thirteen independent nations, with no national executive for enforcing the law. Therefore each state ignored the resolutions from Congress and served its own self-interest. Each state established its own rules for interstate commerce, printed its own money and even established treaties with foreign nations. No system existed for governing the interactions between the states, who often treated each other like hostile powers.

The new nation did possess one thing in abundance, land; the vast wilderness between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River. Conceded by the British in the Treaty of Paris, the Americans looked at this as their economic solution. The nation owed the veterans of the Revolution a huge debt and paid them in the only currency available, land grants. Unfortunately, someone must inform the Indians living on this land and make treaties regarding land distribution.

For the Americans this seemed simple, the Indians, as British allies, suffered defeat with the British and must pay the price. After all, under the rules of European “civilized” warfare, defeated nations surrendered territory and life went on. Unfortunately no one, neither American nor British, informed the Indians of these rules, because no one felt they deserved explanation. Besides, the British hoped that by inciting Indian troubles they might recoup their former colonies.

With British arms and encouragement the tribes of the “Old Northwest” raided the western frontier with a vengeance. From western New York down through modern Kentucky these Indians kept up their war with the Americans. In Kentucky between 1783 and 1790 the various tribes killed an estimated 1,500 people, stole 20,000 horses and destroyed an unknown amount of property.

Our former ally, Spain, controlled all of the territory west of the Mississippi River before the American Revolution. From here they launched expeditions that captured British posts at modern Vicksburg and Natchez, Mississippi, and the entire Gulf Coast. However, they claimed about two-thirds of the southeastern US based on this “conquest” including land far beyond the occupation of their troops. Like the British, they incited the Indians living in this region for keeping out American settlers.

Spain also controlled the port of New Orleans and access into the Mississippi River. Americans living in Kentucky and other western settlements depended on the Mississippi River for their commerce. The national government seemed unable, or unwilling, at forcing concessions from Spain, and many westerners considered seceding from the Union. Known as the “Spanish Conspiracy” this plot included many influential Americans and only disappeared after the American victory at Fallen Timbers.

While revisionist historians ignore the “Spanish Conspiracy” they illuminate land speculation by Americans in Spanish territory. Of course they conveniently ignore the duplicity of Spanish officials in these plots, and their acceptance of American money. In signing the Declaration of Independence the Founding Fathers pledged “their lives, their fortunes and their sacred honor.” Many Continental Army officers bankrupted themselves when Congress and their states proved recalcitrant at reimbursing them for incurred expenses. These officers often personally financed their troops and their expeditions because victory required timely action. Of importance for the western region, George Rogers Clark used his personal credit for financing his campaigns, which secured America’s claim. It takes no “lettered” historian for determining that without Clark’s campaign that America’s western boundary ends with the Appalachian Mountains, instead of the Mississippi River. With the bankrupt Congress and Virginia treasuries not reimbursing him he fell into the South Carolina Yazoo Company. Clark’s brother-in-law, Dr. James O’Fallon, negotiated this deal for 3,000,000 acres of land in modern Mississippi. This negotiation involved the Spanish governor of Louisiana, Don Estavan Miro, a somewhat corrupt official. When the Spanish king negated the treaty, Clark, O’Fallon and the other investors lost their money and grew hateful of Spain.

Another, lesser known, negotiation involved former Continental Army Colonel George Morgan and the Spanish ambassador, Don Diego de Gardoqui. Morgan received title for 15,000,000 acres near modern New Madrid, Missouri for establishing a colony. Ironically, an unscrupulous American, James Wilkinson, discussed later in the document, working in conjunction with Miro, negated this deal.

Both of these land deals involved the establishment of American colonies in Spanish territory, with Americans declaring themselves Spanish subjects. Few Spaniards lived in the area west of the Mississippi River and saw the growing number of American settlers as a threat. However, if these Americans, already disgusted with their government, became Spanish subjects, they now became assets. If they cleared and farmed the land, they provided revenue that Spanish Louisiana desperately needed. Since many of these men previously served in the Revolution, they provided a ready militia for defending their property. This included defending it against their former country, the United States, with little authority west of the Appalachian Mountains.

Internationally, the weak US became a tragic pawn in the continuing superpower struggle between England and France. With no naval forces for protection, American merchant mariners became victims of both nations on the high seas. British and French warships stopped American ships bound for their enemy, confiscating cargo and conscripting sailors into their navies. In the Mediterranean Sea, our ships became the targets of the Barbary Pirates, the ancestors of our enemies today. Helpless, our government paid ransoms for prisoners and tribute for safe passage until the Barbary Wars of the early 19th Century.

Despite all of these problems most influential Americans still “looked inward,” and feared a strong central government more than foreign domination. When the cries of outrage came from the western frontiers regarding Indian depredations, our leaders still more feared a “standing army.” In the world of the Founding Fathers the tyranny of King George III’s central government created their problem. The king further used his “standing army” for oppressing the colonists and infringing on their liberties.

Congress also possessed more recent examples of the problems with a “standing army” during the American Revolution. First came the mutiny of the Pennsylvania Line in January, 1781 for addressing their grievances. Since the beginning of the war, in 1775, the Continental soldiers endured almost insurmountable hardships, as explained previously. The soldiers rarely received pay, and then received the almost worthless “Continental Currency,” which inflation further devalued. This forced severe hardships also on the soldiers’ families, and many lost their homes and farms. The soldiers marched on the then-capital, Philadelphia, for seeking redress for these grievances. Forced into action, Congress addressed their problems with pay and the soldiers rejoined the Army.

A second, though less well known, mutiny occurred with the New Jersey Line shortly thereafter with different results. For “nipping” a growing problem “in the bud,” Washington ordered courts-martial and the execution of the ring leaders. The last such trouble occurred in the final months of the war in the Continental Army camp at Newburgh, New York. Dissatisfied with congressional inaction on their long-overdue pay, many officers urged a march on Philadelphia. Fortunately, Washington defused this perceived threat against civil authority, and squashed the strong possibility of a military dictatorship.

However, Congress realized that it needed some military force for defending the veterans settling on their land grants. The delegates authorized the First United States Regiment, consisting of 700 men drawn from four state militias for a one year period. I read countless sources describing the inadequacy of this force, highlighting congressional incompetence and non-compliance by the states. The unit never achieved its authorized strength, the primitive conditions on the frontier hindered its effectiveness and corrupt officials mismanaged supplies. Scattered in small garrisons throughout the western territories, it never proved a deterrent against the Indians.

No incentives existed for enlisting in this regiment, and it attracted a minority of what we call today “quality people.” Again, confirming state dominance over the central government, this “army” came from a militia levy from four states, a draft. A tradition at the time provided for the paying of substitutes for the men conscripted during these militia levies. Sources reflect that most of these substitutes came from the lowest levels of society, including those escaping the law. From whatever source these men came, at least they served and mostly did their best under difficult circumstances.

Routinely, once the soldiers assembled they must learn the skills needed for performing their duties. For defending the western settlements the small garrisons must reach their destination via river travel. Once at their destination they must often construct their new installations using the primitive tools and resources available. The primitive transportation system often delayed the arrival of the soldiers’ pay and supplies, forcing hardships on the troops. Few amenities existed at these frontier installations and the few settlements provided little entertainment for the troops. Unfortunately, once the soldiers achieved a level of professionalism, they reached the end of their enlistment. With few incentives for reenlistment, the process must begin again, with recruiting and training a new force.

Fortunately many prominent Americans saw that the country needed a different form of government for ensuring its survival. Despite the best intentions and established rules, few people followed these rules or respected our intentions. The Constitutional Convention convened in Philadelphia in May, 1787 with George Washington unanimously elected as its president. As the delegates began the process of forming a “more perfect Union,” the old, traditional “colonial” rivalries influenced the process.

While most Americans possess at least ancillary knowledge of the heated debates among the delegates, few know the conditions. Meeting throughout the hot summer, the delegates kept the windows of their meeting hall closed, preventing the “leaking” of information. We must remember that this occurred before electric-powered ventilation systems or air conditioning. They kept out the “media,” and none of the delegates spoke with “journalists,” again for maintaining secrecy. Modern Americans, often obsessed with media access, do not understand why the delegates kept their deliberations secret.

Most of the delegates felt they possessed one chance for creating this new government and achieving the best possible needed their focus. “Media access” jeopardized this focus and “leaked” information, with potential interruptions, jeopardized their chance for success. We find this incomprehensible today, with politicians running toward television cameras, “leaking” information and disclosing national secrets. Unfortunately a “journalistic elite” exists today, misusing the First Amendment, with many “media moguls” believing themselves the “kingmakers” of favorite politicians.

The delegates sought the best document for satisfying the needs of the most people, making “special interest groups” secondary. Creating a united nation proved more important than prioritizing regional and state desires. These delegates debated, and compromised, on various issues; many of which remain important today. They worried over the threat of dominance by large, well-populated states over smaller, less-populated states. Other issues concerned taxation, the issue that sparked the American Revolution, and import duties, which pitted manufacturing states against agricultural states. Disposition of the mostly unsettled western land, claimed by many states, proved a substantial problem for the delegates. The issue of slavery almost ended the convention and the delegates compromised, achieving the best agreement possible at the time. On September 17, 1787 the delegates adopted the US Constitution and submitted it for approval by the individual states.

Again, merely passing laws and adopting resolutions does not immediately solve the problems, or change people’s attitudes. Ratification of the Constitution required the approval of nine states, (three-fourths) which occurred on June 21, 1788. However, two important large states, New York and Virginia, still debated ratification. Several signers of the Declaration of Independence, and delegates at the Constitutional Convention, urged the defeat of the Constitution. Fiery orator, Patrick Henry, of “Give me liberty, or give me death,” fame worked hard for defeating it in Virginia. Even the most optimistic supporters gave the Constitution, and the nation, only a marginal chance at survival.

Pingback: BATTLE OF FALLEN TIMBERS CONFIRMS AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE-PART II « Frontier Battles