Category Archives: Indian wars

Review of Massacre: Daughter of War

Skjelver, Daniell Mead. Massacre: Daughter of War. Rugby, ND: Goodwyfe Press, 2003.

Skjelver, Daniell Mead. Massacre: Daughter of War. Rugby, ND: Goodwyfe Press, 2003.

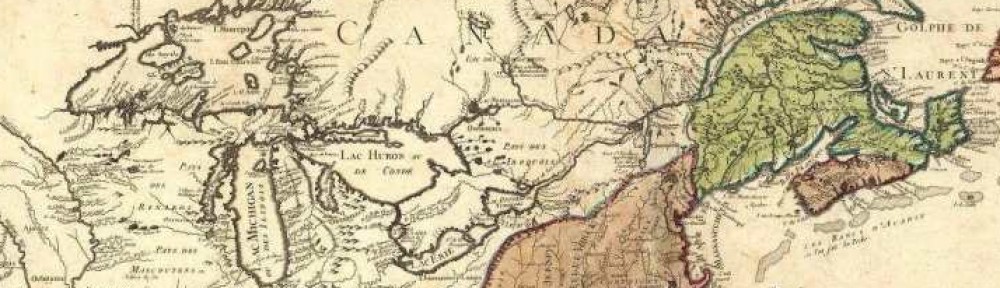

Danielle Mead Skjelver wrote a very skilful novel weaving her family history within the larger events in colonial America during the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, including the tumultuous events of King Phillip’s War (1675-76) and Queen Anne’s War (1702-13). Beginning with the 1637 destruction of the Pequot Fort, the book traces the Hawks/Scott family and its place within the larger Anglo-French conflicts as well as conflicts with Native Americans. Several characters stand out within the story: Sergeant John Hawks, Hannah Scott (the Sergeant’s daughter), Jonathan Scott (Hannah’s husband), John Scott (Hannah’s son), Honors The Dead (a fictional Mohawk warrior), and Red Bear (Honors The Dead’s son-in-law). All of these characters relate to each other as the story progressed and indict Puritan life along the way.

The story of Honors The Dead is a truly remarkable one when considered against Sergeant John Hawks and his family. Taken captive when very young, Honors The Dead witnessed the destruction of his birthplace in 1637, where Sergeant John Hawks’ father participated in the massacre of the Pequot residing there. Honors The Dead sees the Sergeant’s father looking down at him after the death of Honors The Dead’s father, which allowed the boy to see the unique features of the Hawks family, their blue eyes (described as ice blue) and blonde hair. As he grew into manhood among a rival people, Honors The Dead sought revenge against the one he perceived killed his father.

Meanwhile, the Hawks family continued the tradition of serving in the military, as Sergeant John Hawks participated in King Phillip’s War. War was a way of life more than just serving in it, as Hawks soon found out. When Queen Anne’s War erupted in the colonies, Hawks’ daughter Hannah was living in Connecticut Colony raising a young family, while a remarried John lived in Deerfield, Massachusetts Colony. Tragedy struck the Sergeant’s family, as the Deerfield Raid in 1704 claimed several members to outright murder and captivity. Despite this, Hawks begins to recover, living with Hannah and her family. An uneasy peace settles over the family, as they go about the routine of Puritan life, while Red Bear continues on the warpath and avenging his father-in-law’s loss of his first wife and daughters at the hands of the English, including Sergeant Hawks.

Tragedy strikes Hannah’s family as her brother-in-law is tortured and killed by Indians, while Jonathan, and her two oldest sons, John and Jonathan Jr. (known by Junior in the book) are taken captive by Red Bear and his war party. The book then addresses the hardships of captivity, including running the gauntlet and internal conflict within a boy.

While all the main characters are captivating, the character of young John Scott, who is captured at the age of eleven truly stands out. Skjelver described the nature of Puritan life quite well, including the many negatives. Poor John, who was left-handed, was treated harshly in his Puritan community, as they viewed this trait as a predilection towards devil worship and evil. While his grandfather, John Hawks, is a little more gentle with the boy, his Puritan beliefs do surface on occasion. The boy tries hard to please those he loves, but he excelled in areas viewed as bad by Puritans. His father, Jonathan Scott, while initially appearing as a loving father, later comes across as a hard, uncompromising man, a sharp contrast to his mother Hannah, who seems to recognize her son’s unique characteristics, but is prevented from nurturing him to the fullest by the constraints of society. Through Skjelver’s portrayal, one sees the attraction of the open frontier versus the unbending harshness of Puritans.

Young John Scott comes across as a pseudo-Hawkeye, as he is drawn to the wild of the woods and becomes a skilled hunter, which draws the attention of Red Bear. Upon entering captivity, readers will feel the strong conflict within John’s soul, as he takes to Indian life, where he is accepted for who he is. John’s story forces readers to reflect upon their own faith, character traits that may contrast with their community, and how they might handle such a situation. Through the story of the Hawks/Scott family, Hannah is truly a “daughter of war”, suffering such loss that few women could endure.

Danielle Skjelver’s prose was solid, descriptive, and truly captured the cruelties of warfare and the strength of the human spirit. Given her current graduate study in History, it is no doubt that she will one day make her mark in historical scholarship. Though the story is different and involves an earlier period, Massacre: Daughter of War is a wonderful fictional account based around real events and serves as a twenty-first century model of Last of the Mohicans.

BATTLE OF FALLEN TIMBERS CONFIRMS AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE-CONCLUSION

The Indians lost many of their leaders in this fight and those remaining lost their enthusiasm with the British betrayal. Facing a well-trained and disciplined force, something the Indians never before experienced, they withdrew when overwhelmed. Chased by mounted soldiers, who struck them down with sabers, the retreat became a rout. When the British troops at Fort Miamis closed the gates, literally in their faces, their morale collapsed.

I previously mentioned the desire for peace by Little Turtle before the battle; he did not counsel peace alone. American renegades and Loyalists persuaded many reluctant Indians into engaging the Americans in combat. Particularly the previously mentioned Alexander McKee, who tried rallying the defeated Indians behind Fort Miamis. This lasted only a few minutes as they broke again and headed for their families camped some distance away. A week after the battle McKee tried rallying them with the uncorroborated story of the American troops desecrating the Indian graves. This possibly occurred given the years of hatred between the “long knives” and the Indian tribes, but nothing official mentions it. Even this horrific story did not inspire revenge in the face of the American victory and British inaction.

Wayne eventually regrouped his Legion at the previously established Fort Defiance after a difficult march. The only Indians the soldiers encountered scavenged through vacated American campsites, searching through abandoned items. Wayne believed these represented scouts for a new Indian advance; however, they merely searched for food and other necessities.

At Fort Defiance the Legion rested and refit, anticipating another battle with the Indian confederacy, and possibly the British. Wayne now concentrated on what we call today an “after action report” and a report for Secretary Knox. Not every soldier acted bravely and with honor during the battle and he commenced several courts-martial. Records exist of the trials of at least two junior officers and at least two enlisted men for “leaving their posts.”

The soldiers, as all soldiers in all times, immediately wrote their families and friends that they survived the battle. And as all soldiers, they probably embellished their roles in the battle, however we must forgive them this weakness. Truthfully, these men volunteered and advanced against an enemy who previously defeated two expeditions, the last one a disaster. They further described the new territory they explored and the Indian settlements they subsequently destroyed.

One thing unforgivable, the secret dispatches Wilkinson sent, criticizing Wayne and deliberately lying about Wayne’s conduct of the campaign. This merely continued Wilkinson’s continuing conspiracy against Wayne, and the newspapers eagerly published them. Officers of the “Wilkinson camp” continued writing anonymous letters and stoked controversy in Philadelphia. Fortunately, both Washington and Knox wrote letters expressing their support for Wayne and openly defended their Revolutionary War comrade.

Another unforgivable situation occurred with many of the residents of Cincinnati against the American allies, the Choctaw. Although they did not participate in the final battle, the defeat of their enemies ended their service. They returned home “with honor” for telling of their bravery among their brethren, who stayed home. They reached Cincinnati among rumors that they brought with them a white female child, “naked bound, and suffering.” Unfortunately only one of them spoke a little English and he proved inadequate for explaining away this rumor.

Winthrop Sargent, the acting governor of the Northwest Territory, investigated the rumor, but found no evidence that this child existed. Whipped into a frenzy by free-flowing liquor many of the local men, who did not join the campaign, armed themselves against the Choctaw. They attacked and injured several of these warriors and searched their camp for the non-existent child.

Sargent called out the Cincinnati militia, which proved inadequate, and probably unwilling, at defending the Choctaw from the mob. He then requested help from Captain John Peirce, who commanded the small federal garrison at nearby Fort Washington. Peirce dispatched a detachment of regulars for guarding the Choctaw camp until they departed Cincinnati. Sargent met with the Choctaw and assured them of the “sincere Friendship of the united States,” and punishment of those involved. However, the shameful actions of the territorial judiciary only indicted two men, and those escaped any punishment for their crimes. Unfortunately, such shameful conduct continued throughout the American nation’s interactions with its first citizens, even those who served as allies.

While the “courageous” men of Cincinnati vented their anger on the friendly Choctaw, the Legion’s contact with hostiles virtually ended. Fort Defiance existed in the heart of the Auglaize camps, making this area useless for the hostile tribes as a base of operations. However, it set at the end of a very precarious line of communication, hindered by the wilderness terrain. Wayne struggled for getting his troops the proper supplies, and kept his quartermaster department as busy as before.

Meanwhile the troops of the Legion suffered from the boredom and inactivity suffered by all soldiers following the battle. Throughout military history we find evidence that soldiers with “too much time on their hands” often contemplate too much on their circumstances. This proved particularly troublesome with Scott’s Kentuckians, hardly the model for discipline in the first place. They eagerly anticipated their approaching discharges and resented the labor involved in fortifying Fort Defiance and other routine camp details.

Wayne tried keeping them busy with scouting missions and escort duty for supply convoys; however they performed these duties haphazardly. With the August 31st report showing 1,611 Kentuckians serving in some capacity with the Legion, they proved excellent at consuming provisions. Their repeated acts of insubordination frustrated the lenient attitude of Scott toward his fellow Kentuckians, who court-martialed an unknown, but high, number.

Even the regulars experienced this declining morale, as much from the indifference and insufficient support from Congress as from the fatigue details. As the Legion advanced against the Indians a steady stream of discharged soldiers and deserters left the column. No “stop loss” existed at that time and when soldiers reached the end of their enlistment, they simply left. With no incentive for reenlistment, and reduced pay from the parsimonious Congress, critically needed veterans left the service.

All of this placed Wayne at a serious disadvantage deep in enemy territory, or so he thought. Although he sent out extensive scouting parties, they encountered no Indian or British activity. Before Napoleon’s military strategy became legendary, Wayne employed one of Napoleon’s maxims, summarized, “in the absence of adequate intelligence, always assume your enemy will do the correct thing.”

Because of the length of time that the army stayed at Fort Defiance, the large number of troops soon depleted the captured Indian food stocks. Many men grew sick eating unripe vegetables as they lived on half-rations of meat and flour. By September 10th foraging parties ranged almost fifteen miles in search of food. Part of the supply problem occurred because of the declining health of packhorses, forcing the abandonment of their cargoes.

Quartermaster O’Hara soon made numerous journeys up and down the line of communication for fixing this problem. Wayne sent his contractors a scathing letter about the inadequate amount of supplies arriving in his camp. He further offered the mounted Kentuckians three dollars for every hundred pounds of flour they carried forward, deducted from the contractors’ payments.

Despite his mounting problems, Wayne developed plans for constructing another fort deep in the heart of the Indian country. Following detailed reconnaissance Wayne decided on moving his command near the old village of Kekionga. However, he must first ensure that his quartermaster department knew of this move and forwarded adequate supplies. For this he depended on Scott’s Kentuckians, who still served as a mounted force, although the health of their horses declined.

Wayne then took a gamble and offered the Indians a chance for peace, releasing the captured Indian women with a message. In this message he reminded the Indian chiefs of their “wrong choices” and offered a “path for peace.” He suggested a conference and exchange of prisoners as a sign of “good will,” and “fair & equitable terms of peace.”

Without waiting for a reply Wayne left a significant garrison at Fort Defiance, supplemented by a large number of sick and wounded. He left command of the post under Major Thomas Hunt and about 200 men “fit for duty.” The remainder of the Legion marched southwest on the northern bank of the Maumee River on September 14th in a steady rain. After a hard march, in which part of the command became lost, they arrived near Kekionga on September 18th. Observers called this the largest Indian village in the region with about 500 acres of land cleared for agriculture. Here Wayne selected the site for his new fort, Fort Wayne, again near modern Fort Wayne, Indiana. He further dispatched Barbee’s Kentuckians for bringing forward supplies from Fort Recovery on September 20th.

While Wayne’s men constructed Fort Wayne, Hunt forwarded four British deserters from Fort Miamis. They reported that the British did try reinforcing Fort Miamis, sending a company of the 5th Regiment of Foot and some Queen’s Ranges from Fort Niagara. Upon arrival the British soldiers found Fort Miamis surrounded by the Americans and retreated toward Fort Erie. They erroneously reported that 1,600 Indian warriors camped eleven miles northeast of Fort Miamis along Swan Creek. The British Indian Department records indicated issuing provisions for 2,500 Indians, with only 860 as warriors. However, Wayne did not know this and must take the proper precautions for his rapidly shrinking Legion. The deserters also mentioned that about 25 American deserters arrived in Fort Miamis providing the British with intelligence.

The lull in operations also provided Wayne opportunities for sending Knox an updated report of his intentions and his problems. Of importance he emphasized the problems of supplying his force in the field, something that always hindered western operations. He further informed the secretary of war of the pending resignation of one of his critical contractors, Major John Belli.

Wayne further mentioned the critical problem with expiring enlistments, particularly in the longest serving units, the 1st and 2nd Sub-Legions. Previously the 1st and 2nd US Regiments, the bulk of these men enlisted for the St. Clair expedition in 1791. He pointed out that within six weeks time each of these units might number no more than “two companies each.” Furthermore most of the enlistments of the 3rd and 4th Sub-Legions expired in the coming summer of 1795. He described his Legion as “nearly Annihilated” by expiring enlistments, forcing the abandonment of “all we now possess” in the West.

Looking back from the advantage of hindsight and knowing the situation of both sides me may dismiss Wayne’s concerns. However, he sat on the farthest reaches of American “civilization,” indeed beyond that civilization in the middle of enemy territory. Furthermore, he must send his reports and receive his orders from distant Philadelphia using horses and man-powered boats.

Creating additional problems, when Barbee’s men returned with the supply convoy, it brought with it several sutlers. These sutlers brought with them live cattle, sheep and other supplies for purchase by the soldiers. Unfortunately the soldiers lacked money with their pay not arriving, and often engaged in stealing. The sutlers also brought a significant amount of liquor, which further increased the disciplinary problems.

Again, the Kentuckians proved the worst of the offenders because they demanded their discharges, although their enlistments continued until November. Since the days of the Viet Nam War many stories endure regarding “short-timers,” those soldiers ending their tours of duty. These “short-timers” traditionally feel themselves above military discipline and often “push the envelope” with their conduct. The Kentucky militiamen, living on half-rations and fortified by liquor, often refused the orders of their officers and bordered on mutiny. Wayne visited their camp and told them “what they might expect should they disobey his order.” However, only a few officers and men followed Barbee on his next escort mission on October 10th.

Barbee’s men returned on October 12th with only enough rations for three days and Wayne made another gamble. He decided that his Kentucky militia served no further purpose and he informed Scott of his intention of sending them home. The Kentuckians departed camp on October 14th leaving Wayne with fewer than one thousand regulars. The homesick Kentuckians made good time on their return arriving at Fort Washington on October 20th. One unnamed regular stated that Scott’s men “rendered their Country more Services than any Volunteers have done before.” One may determine whether the soldier intended this as a compliment, or sarcasm regarding how he felt about these men.

On October 27th the Legion marched at sunrise bound for Fort Greenville leaving Hamtramck in command with about 300 men. Hamtramck issued his first order, naming the new post Fort Wayne and his men settled into their new quarters. Meanwhile the Legion marched back along the road they previously cut with the weather turning cold and frosty. The Legion reached Fort Greenville, and winter quarters, on November 3, 1794 amid the cheering of the garrison. Celebrations by both officers and enlisted men lasted until midnight and morale miraculously appeared very high. Gaff records the accurate prophesy of one soldier, who entered in his journal, “AMERICA! What glorious Days mayest thou soon hope for, when thy Armies shall excel the Veterans of Alexander-thy Fleets command the Ocean and give Laws to the World.”

Upon establishing winter quarters, Wayne tried reducing his quartermaster problems as much as possible. First he discharged as many of the scouts as possible, including the valuable Wells, whose wound permanently disabled him. When the scouts returned home they received heroes’ welcomes wherever they appeared, as did anyone who served in the Legion.

Veteran soldiers continued leaving the Legion when their enlistments expired and officers asked for furloughs. As these men journeyed home they received heroes’ welcomes wherever they went for achieving the independent nation’s first military victory. An adequate historical analogy may compare the celebration of these veterans with that received by those returning from World War II. The western settlers rejoiced that finally, after almost twenty years, someone decisively defeated the Indians. Furthermore, the faraway federal government addressed one of their major problems, seriously damaging the secession movements.

For all the jubilation felt among the American settlers, the Indians felt totally broken by their defeat. In a period of less than two hours they degenerated from an invincible fighting force into a defeated and routed mob. The great Miami Confederacy dissolved as the defeated tribes returned home, those who still possessed homes. Those who previously lived in the path of Wayne’s Legion found their villages unattainable, now occupied by American troops. With their villages and crops destroyed they faced a harsh winter surviving through the largess of the British. The betrayal by the British at Fallen Timbers made them doubt the reliability of receiving sustenance from them. They must seek terms with Wayne for ensuring the survival of their families, even at the cost of much of their land.

On December 17, 1794 a small group of French Canadians and Indians approached Fort Wayne for a conference. Within two weeks delegations from the Pottawatomie, Chippewa, Wyandot and Ottawa arrived and promised peace. The Miami arrived in the middle of January, 1795 seeking terms as their tribe faced starvation. Only the Shawnee and Delaware, strongly under the influence of the trader, McKee, remained reluctant.

Finally on February 7, 1795 Wayne received a delegation of Shawnee and Delaware led by the war chief, Blue Jacket. As the tribes that preceded them they signed a truce on the frontier and promised no further hostilities. Wayne scheduled a grand council for June 15, 1795 for ensuring the participation of as many hostile tribes as possible. He further allowed the resettling of those Indians in their destroyed villages near the forts that dominated the terrain.

The late arrival of some of the tribes delayed the grand council until July and required several weeks of ceremony. Participating tribes included the Wyandot, Delaware, Shawnee, Ottawa, Chippewa, Pottawatomie, Miami, Eel River Miami, Wea, Kickapoo, Piankashaw and Kaskaskia. Some of these tribes did not join the Miami Confederacy and previously established peace with the Americans; however they desired further peace.

Known as the Treaty of Greenville it established an almost twenty-year period of peace between the settlers and Indian tribes. It further surrendered most of the modern state of Ohio as well as locations for military forts on Indian land. In return the Indians received a one-time grant of goods worth $20,000 and an annuity worth about $9,500. Subsequent articles addressed hunting rights, trade and establishing a system of mediating complaints between the parties.

It further broke the hold the British held on the region and American traders established posts among the tribes. Little Turtle regained some of his former prestige in peace and became an advocate for allying with the Americans. He subsequently visited three American presidents, Washington, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson and received the treatment of a foreign dignitary.

Wayne journeyed east almost immediately following the signing of the treaty for several reasons. With the fighting over and his troops engaged in mostly routine work the time seemed ripe for this visit. First he lobbied in Congress for the ratification of this treaty without relying on messengers. Second he contradicted the stories, mostly circulated by Wilkinson, of his mismanagement of the Legion and the campaign in general. Third, he hoped for circumventing the efforts of some members of Congress for reducing the size of the Legion. It seems that the Congress always traditionally, and irresponsibly, reduces the size of our military forces without considering the strategic implications. On a personal level, Wayne hoped that he might succeed Knox as Secretary of War.

Meanwhile on the international front the US achieved some diplomatic success against its immediate foreign threats, England and Spain. With both nations at war with France since 1793 they did not need a war with the US. On November 19, 1794 Chief Justice John Jay signed what historians now call the Jay Treaty with England. This treaty merely confirmed most of the terms of the original peace with England in 1783, however now England followed them. The most important, they evacuated the military posts they illegally held and removed their control over American territory.

With the knowledge of Jay’s Treaty, Spanish officials began negotiations with Thomas Pinckney, the American ambassador for England. Spain previously suffered some military defeats in the Caribbean and did not need another war in the region with the US. On October 27, 1795 both nations signed the Treaty of San Lorenzo, sometimes called Pinckney’s Treaty. It surrendered military forts that Spanish troops occupied in American territory, and opened the Mississippi River for commerce. It further provided American merchants with duty-free transportation through New Orleans, which delighted the western settlers.

Historians may argue that events in Europe forced the negotiations for these two treaties; regardless of Fallen Timbers. However, I believe that this demonstration of American power strongly influenced these two nations into defusing a potential “second front” neither of them needed.

Wayne achieved some success during his Philadelphia visit, and received a hero’s welcome, even from his critics. The Senate ratified the Treaty of Greenville on August 3, 1795 and Washington signed it on December 22nd. This occurred before Wayne’s arrival in Philadelphia, on February 6, 1796, and he then focused on the other issues. With his popularity, Congress avoided any criticism of his conduct as commander-in-chief of the Legion. He further won concessions regarding the post-war strength of the military forces: four regiments of infantry, two companies of dragoons and one “corps” of artillery. This force became known as the United States Army, effective on October 31, 1796, with few other changes.

However, Washington did not select Wayne as Secretary of War because of his “financial troubles,” and selected James McHenry. Described by Jacobs as someone “Without unusual talents,” McHenry possessed “considerable means,” meaning he did not need the low salary.

Upon achieving success Wayne returned west, for continuing his duties and supervising the peace. When he arrived at Fort Greenville he found Wilkinson, who now desired a journey east. Wayne performed his duties on the frontier, including the occupation of Detroit and other posts evacuated by the British. He further addressed the supply problems of both his troops and the Indians, now under his care.

Meanwhile Wilkinson collected evidence against Wayne, mostly false, and renewed his charges against Wayne. He found allies among his political cronies, mostly from western delegations, and tried damaging Wayne’s reputation. Furthermore, Wilkinson did not like McHenry, describing him as a “mock minister,” and used his recent appointment against him.

Unfortunately Wayne died on December 15, 1796 while at Fort Erie and, like a true soldier, requested burial at the foot of the flagpole. Mercifully, he did not know of the treachery Wilkinson planned for him, or at least no historical source references it. When he learned of Wayne’s death, Wilkinson wisely withdrew his charges and McHenry easily granted his request. Wilkinson now achieved his ambition and became the new commander-in-chief of the Army, his tenure as troubled as the man.

Wayne, like Patton, died before his laurels faded and without the spectacle of a public investigation. Also like Patton, he revealed himself as a controversial and somewhat eccentric figure with many critics. Both men proved themselves strict disciplinarians, accepting only the highest standards and military geniuses of their own right. Perhaps the greatest endorsement of both men, soldiers who served with them bragged of this service for years afterward. Unfortunately today few Americans know of the great service Wayne gave his country, both during the Revolution and the Indian war.

The Battle of Fallen Timbers did not solve all of America’s problems, but it did guarantee the young nation’s survival. It further established the power and authority of the new constitutional government and thwarted the secessionist movements. Through the use of military force, the nation defended its frontier settlements from the depredations of Indian raids. It further ended the unhindered movement of foreign agents sowing mischief through American territory. The victory also provided a measure of respect from those foreign nations, who previously sought our destruction.

Domestically, most Americans realized a new pride in their nation, and its new form of government. While they still suspected the power of governments, they appreciated its power in defending them. They further accepted the supremacy of federal law in regional and interstate differences, perhaps grudgingly, but they accepted it.

With the Indian threat subdued for the time, a tide of migration across the Appalachian Mountains almost tripled the population of the West. The main road through the mountains from Bedford, Pennsylvania became a thickly settled major highway. Pittsburgh became the “gateway to the Ohio Valley” and experienced good economic times from the increased value of land. Hundreds of boats traveled the Ohio River in safety and settlers cleared both riverbanks without fear. An economic boom transformed former frontier settlements like Pittsburgh, Cincinnati and Louisville into booming cities.

This economic boom benefited the entire country as western residents advertised in the East for “skilled tradesmen.” With the promise of “work plenty, and good wages” these skilled workers developed the vast natural resources of the region. Furthermore, within a few years western farmers developed the fertile land into a dominant agricultural region. Eastern markets flourished from the western development as did the transportation industries, and all associated enterprises.

Therefore, Wayne’s victory at Fallen Timbers made the United States of America a united, politically solvent nation. It furthermore created the conditions for economic solvency as well, and the US Treasury no longer sat empty. July 4th marks the day when American leaders formalized their break with England, like when a somewhat naïve adolescent leaves a parent’s home. August 20th marks when we made the world accept our independence, as when the adolescent earns the respect of adults. The US proved itself capable of self-government, defending its citizens, establishing its sovereignty and meeting the challenges of a harsh world.

The Americans that lived in our new nation survived economic hard times, domestic disputes, a “war of terror,” foreign threats and an uncertain future. Our military personnel of that time suffered immense hardships in a “foreign” land facing a competent, ruthless enemy. They further faced administrative mismanagement, insurmountable logistical problems, political interference and dissensions among their leaders. Furthermore, they recently experienced a devastating defeat in which about half of the force died a hideous death. Yet more Americans volunteered, suffered the hardships and defeated this competent enemy in a quick, decisive victory.

I strongly recommend that we maintain July 4, 1776 as our national Independence Day and that we enthusiastically celebrate it. However, I recommend that we celebrate August 20, 1794 as the day that our nation reached maturity and self-reliance. Without the victory at Fallen Timbers the future growth of the US remains doubtful, and even its independence seemed at risk. Wayne and his troops established America’s perseverance in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds and deserve a place of respect in our history.

Today our history educators barely acknowledge the challenges faced by the newly independent United States of America. Furthermore, it almost never mentions the individuals who met these challenges, and whose sacrifices overcame them, unless it disparages them. Our failure at understanding these challenges does not prepare us for our current, and future, challenges. These individuals bequeathed on us a promising national future and our challenge becomes maintaining that national promise for future generations.

BATTLE OF FALLEN TIMBERS CONFIRMS AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE-PART IV

Wayne arrived upon the completion of the fort and conducted a dedication ceremony, thanking the soldiers for their work. Following the dedication Wayne departed with most of the soldiers for Fort Greenville, leaving two infantry companies and an artillery detachment as garrison. He cautioned the post commander, Captain Alexander Gibson, for keeping out “constant & proper patrols,” and scouting the Indian villages.

The Indians took insult from the occupation of the St. Clair battlefield, ground that they considered sacred. If they allowed the presence of Fort Recovery and its garrison it showed a “loss of face,” for their warriors. Besides, this fort moved the threat from the American soldiers even farther into the heart of their homeland. Miami emissaries journeyed great distances for securing alliances from other tribes against the hated Americans. Desperate, some demanded that the British support them directly with troops in the field.

While the Indians assembled an army for meeting the American army, Wayne pleaded for more troops. Bureaucratic “red tape” and congressional interference did not begin with the current war against terrorism. In the Army of General Wayne the Senate must approve all promotions for officers, ensuring that each state received its portion. Some of these promotions dated from February and March of 1793, hardly conducive for effective leadership of the Legion. Of course the Senate disapproved of many of Wayne’s selections and selected their political favorites.

Congress did authorize an increase in numerical strength, just not for the Legion on the frontier. It approved a “Corps of Artillerists and Engineers” of four battalions for defending the eastern seaports. Concerned with the continuing war in Europe, and Royal Navy ships hovering outside American harbors, Congress authorized the fortification of our seaports. For reducing military expenditures Congress made this “corps” part of the authorized 5,000 for the Legion. This highlights another tradition of Congress, believing they know the nation’s military needs better than commanders in the field.

When spring of 1794 arrived intelligence showed an increase in Indian activity, and British advances into American territory. Patrols around Fort Recovery captured several Indian scouts who provided valuable information of the assembling Indian army. The British constructed a new fort, Fort Miamis, on the Maumee River near modern Toledo, Ohio. Built on the site of a previous British fort abandoned in 1783, the British justified this reoccupation as a Detroit “dependency.”

The massive Indian army of over 2,000 warriors began assembling at Grand Glaize in mid-June, 1794. They further demanded that all “white men either English or French residing among them or getting their livelihood through the Indian Trade…immediately join the Indian Army.” Fourteen British officers from Detroit, dressed in frontier garb, joined these Indians as “observers” because the Indians gave them no choice.

Because food and provisions began running short from the increased number of Indians assembled, they moved toward Fort Recovery. As they traveled the large number required that they kill all the game in their path. This further created desperation as the Indians must replenish their scant supplies from the captured American fort. Therefore, they must capture the fort, or they and their families faced some very hard times.

Wayne experienced more good fortune as a detachment of Chickasaw and Choctaw joined him about this time. These tribes, enemies of the Miami for years, eagerly joined the Americans and scouted toward the Grand Glaize encampment. Forty-five Choctaw and ten white scouts encountered the advancing Indian army on June 26th. They retreated and on June 28th warned Wayne the Indians “in great force and advancing,” with “a great number of white men.”

Furthermore, on the evening of June 29th a mixed company of Chickasaw and Choctaw tried informing the Fort Recovery garrison of the Indian army. Unfortunately none of the Indians spoke English and tried using sign language for communication. Fortunately Captain Gibson prudently took precautions by sending out patrols; however they found nothing.

Outside the gates of Fort Recovery a supply convoy of about three hundred horses bivouacked overnight. They previously delivered supplies and prepared for their return trip for the safety of Fort Greenville. The previously mentioned Major McMahon commanded this convoy and the escort included over 150 troops. At seven o’clock on the morning of June 30th the soldiers and civilian contractors prepared for their return.

Suddenly shots rang out as the Indians attacked the unsuspecting train of packhorses causing a stampede. McMahon, mounted on a horse, tried forming his men for battle when he fell dead from a bullet wound in his neck. For once, the soldiers did not panic, although they withdrew hastily toward the fort against the overwhelming odds. Gibson even sent some of his men from the garrison as reinforcements for McMahon’s men. These few men actually beat back the initial attack with their bayonets until forced back inside the fort.

The Indians surrounded the fort and used the cover of cut tree stumps for firing on the soldiers. Inside the fort the soldiers kept up a “galling fire,” as an unnamed British officer recorded. The soldiers made good use of the recaptured artillery pieces, which proved a tremendous psychological weapon on the Indians. While most Indians willingly endured small arms fire, the artillery proved too much, without their own guns.

Ironically, the Indians expected the previously hidden cannon for use against the American fort. A British artillery detachment from Fort Miamis accompanied the Indians and brought with them several packhorses loaded with ammunition. Later reports stated that the Indians spent several hours unsuccessfully searching for the hidden guns. Fortunately for the Americans, Wayne specifically ordered the search for these guns during the construction of Fort Recovery.

The Indians lost the initiative and kept up a continual fire on the fort throughout the day. An unnamed British officer expressed his disgust with this tactic, and stated that it only “run up their own casualties.” A further demoralizing fact, an unknown number of Chickasaw and Choctaw got behind the Miami confederacy and engaged them from the rear. With so many new tribes recently joining the Miami, they did not know each other and accused each other of fratricide.

Discouraged, the Miami tried one last surprise attack after dark, with no better results than during the day. A few warriors fired on the fort early the next morning with no enthusiasm and then fell back into the woods. Discouraged and running low on food the massive Indian army began breaking up and leaving the field. Several tribes concluded that they fulfilled their commitment for the alliance and went home. With their numbers significantly reduced by these departures, the other Indians went home. They suffered about forty killed and about one hundred wounded and left the field a demoralized force.

Inside the fort the soldiers and civilian contractors suffered nineteen killed, thirty wounded and three missing. Burial details sent outside the fort discovered the mutilated bodies of those killed during the initial assault. Despite their high casualties the men of Fort Recovery felt proud that they beat back this attack of a vastly superior force. Gibson sent Wayne a jubilant message on July 2nd announcing the victory.

Wayne immediately dispatched reinforcements and replenished the fort’s supplies the next day. He also sent a congratulatory message for the troops and lamented those lost during the battle. When Wayne visited the fort about one month later he personally thanked every soldier present. The momentum changed, the soldiers withstood almost impossible odds and defeated the vaunted Miami Confederacy.

News of the victory spread quickly on the frontier and made Independence Day celebrations even more exuberant. In Cincinnati the public toast included the names of the officers killed at Fort Recovery. Western settlers, previously scornful of the federal government, jubilantly toasted “Washington, Congress, cabinet officers and foreign ministers, and American women.” Others toasted Wayne, the Legion and “the heads of the various staff departments.” In Kentucky they toasted the Kentucky volunteers, even though they did not participate in this battle.

Scott’s Kentuckians began assembling at Fort Washington in late May and departed for Fort Greenville on July 20th. They began arriving at Fort Greenville on July 25th and the Legion prepared for movement into Indian country. The Legion left at eight o’clock on the morning of July 28th amid a flurry of drums, fifes and bugle calls.

Once the Legion passed Fort Recovery they must cut their own road through the wilderness, which significantly slowed their march. It further required the detachment of “pioneers,” men selected from each company and armed with axes. In those days no “combat engineers” existed forcing the use of detailed soldiers, or hired civilian employees. Wayne ordered the building of a road thirty feet wide, which required significant labor, and frequent rotation of these “pioneers.”

The Legion continued advancing using all the security measures that Wayne required, including fortified bivouac sites at night. Indian scouts still lurked around the column looking for opportunities for picking off stragglers or stray horses. However, no one straggled and no animals wandered loose, under threat of summary execution. Wayne further ordered the construction of forts at strategic locations along the route, each requiring a garrison.

As the column advanced an incident occurred that jeopardized the success of the expedition, the disappearance of Robert Newman. Newman, a hired surveyor, left camp telling the guards that he departed under the orders of Quartermaster O’Hara. Tracked by Wells himself, the scout captain found where Newman fell into the hands of about four Indians. O’Hara emphatically denied giving Newman such orders, and Wells found no sign of struggle, making Newman at least a deserter. Wayne quickly denounced Newman as a “villain” and capable of giving the enemy “every information in his power” regarding the Legion.

Other officers in the Legion expressed divided opinions regarding Newman’s disappearance, and many believed him a British spy. Historical sources differ on Newman’s status and the first British source labeled him a “deserter” when he reached Grand Glaize. When he arrived at Detroit the British believed him an American spy sent “to deceive” them. They based this on their experiences with other “deserters” sent among them for gathering intelligence.

Newman eventually saw Canada’s lieutenant governor, John Simcoe, the former commander of the Loyalist Queen’s Rangers. Under interrogation, Newman revealed much of what he knew of Wayne’s plan, including a very accurate date regarding the Legion’s arrival in the Indian camp, August 17, 1794. Based on Simcoe’s account, Newman further stated that Wayne intended an attack on any British post on American soil. However, Newman denies this claiming, “I knew nothing of Gen. Wayne’s orders, or what Congress directed him to do.”

Miraculously the British released him and he reentered the US where he published an account of his “capture” in New York’s Catskill Packet. At Philadelphia he boldly walked into the War Department and proclaimed himself an Indian captive, fortunately for him during Secretary Knox’s absence. As a civilian employee no one suspected him of desertion, let alone treason, and he received twenty dollars for his journey home. A few days later Wayne’s dispatch reached Philadelphia and eventually the commander at Pittsburgh arrested Newman.

Interrogated by Wayne, Newman revealed his real purpose, and it eventually involved Wilkinson and intrigue with the British. The story goes that Wilkinson entered into a corrupt scheme with some of the contractors for enriching themselves by continuing the war. It seems that one of the contractors, Robert Elliott, possessed a brother in the British service, Captain Matthew Elliott, currently at Grand Glaize.

Alarmed at this treachery, Wayne began rooting out other traitors as well, including the other surveyor, Daniel Cooper. Cooper admitted that he wrote an incriminating letter found lying on the roadside, but later recanted his confession. However, both he and Newman remained in custody until after the campaign, with their ultimate fate unmentioned in my sources.

No hard evidence existed against Wilkinson, and he continued as second-in-command throughout the campaign. However, the Wayne-Wilkinson feud worsened with Wilkinson looking at any remark as an insult. He kept a journal of all of Wayne’s criticisms of him, and history mostly proves Wayne correct. Lieutenant Hugh Brady commented that “Wilkinson was jealous of W. could not be second and was worth nothing when he got to be first.”

An accident almost ended Wayne’s life on August 3rd, when a large beech tree fell on his tent. This put the camp in great confusion as reports of the general’s death spread rapidly, and thankfully erroneously. An old stump absorbed most of the force and Wayne suffered an injured left leg and ankle. Upon examination someone carelessly kindled a fire near the tree and it toppled over. History records the event as an accident; or did Wilkinson possess enough hatred for arranging the accident? Suppose Wayne died and Wilkinson assumed command, again, did he possess the qualities necessary for winning victory? Did he connive with the British for prolonging the war for paying off his rumored gambling debts with bribes?

While Newman told British officials three different stories, Wayne continued his advance, uncertain of Newman’s adventure. In early August the Legion passed through several deserted Indian towns and the soldiers upgraded their rations with the abandoned crops. As the troops advanced up the Maumee River they encountered an increasing number of Indian towns and a fertile valley. Surprisingly they found few Indians as they advanced toward the main Indian camp of Grand Glaize. They did not know that Newman informed the British of Wayne’s advance on Fort Miamis, and most of the Indians departed for there.

Wells and his scouts continued their intelligence gathering, bringing in prisoners each day with fresh information. As their exploits became legend among the soldiers, the scouts always tried outdoing themselves. Unfortunately, their luck ran out one day when they tried capturing fifteen Delaware by deception. Wells and one of his officers, Lieutenant Robert McClellan, received serious wounds that took them out of the campaign. From one of Wells’ Shawnee captives Wayne confirmed Newman’s treachery, eleven days after his desertion.

At Grand Glaize, Wayne built Fort Defiance, for denying the Indians this sanctuary and proving his power. Here he sent the Miami Confederacy one last offer for peace through one of the recent Shawnee captives and one of his scouts, Christopher Miller. A heavy rain delayed the advance of the Legion from this fort for two days longer than Wayne anticipated. The recent rain hindered their march as both men and animals became mired in the mud. Several accounts state that the march more resembled a mob than a military formation, but the advance continued.

The weather and rough march also deeply affected Wayne’s suffering from gout, however he still insisted on riding a horse. His pain also made him even more short-tempered, causing more resentment with Wilkinson and other officers. His demeanor improved somewhat with the return of Miller with the Indian response regarding his peace overture. The message contained some deception as the Indians asked for time for considering Wayne’s offer. In reality they wanted the time hoping that more warriors from the Pottawatomie might arrive from Detroit.

Eager for action, Wayne dismissed the call for time and began his advance the next day entering a thick wooded area. They encountered some of the roughest terrain yet and reached the rapids of the Maumee River, finding the river about six hundred yards wide. Here American scouts began engaging the Indian scouts and Wayne camped for the night. He delayed the advance until he successfully scouted the terrain ahead, and now lamented the loss of Wells.

Following sufficient reconnaissance Wayne ordered an advance on August 18th and encountered an increasing number of Indian towns. Here the soldiers found themselves astonished at the number of well-constructed cabins and storehouses. They further found a silversmith’s shop and books containing thirty years of accounts and extensive connections with Detroit. Several of the stores showed the ownership of French traders for over one hundred years.

While Wayne advanced turmoil and indecision surfaced among the Indian alliance, and even Little Turtle changed his mind. The battle at Fort Recovery shocked him regarding the Indian chance for victory against the entire Legion. Attending a council in July at Detroit he tried unsuccessfully for obtaining direct British military action. The British symbolically reinforced Fort Miamis and a company of Detroit militia joined the Indians. However the British commander at Detroit, Lieutenant Colonel Richard England of His Majesty’s 24th Regiment of Foot (Infantry), made no promise of direct participation by British troops.

In early August a delegation of Wyandots presented England with the “war hatchet” originally given them during the Revolution. They demanded that England “rub off the rust” and join them in defending their homeland from the Americans. If not, the Wyandot promised no help if the Americans attacked Fort Miamis and Detroit. With no authority, England merely alerted his command of the impending American threat and prepared for attack.

With his assembled Indian army running short of food and other provisions, Little Turtle began contemplating Wayne’s terms. He further understood that the approaching American force outnumbered his dwindling number of warriors. The unsuccessful attacks further proved that the Indians faced a competent commander and better quality troops than previous expeditions. Even the arrival of a contingent of Mohawks, from the supposedly peaceful Iroquois, did not encourage Little Turtle.

When Little Turtle counseled peace he lost his charisma among the confederation, and his position of leadership. Experiencing nothing but victory against the American forces, they did not heed his warning. Little Turtle saw the future, that while the Indian alliance defeated each American expedition, another came the next year. He further saw that each expedition increased in the number of soldiers sent against them, while the Indian numbers reduced.

Accused of cowardice, a Shawnee chief named Weyapiersenwah, Blue Jacket in English, emerged as the new leader of the Miami Confederacy. Historians know little of Blue Jacket’s early life, since he only enters history as a grown warrior. Rumors in the 19th Century named him as a white captive named Marmaduke van Swearingen, popularized by historical novelist Allan W. Eckert. Supposedly DNA testing of descendants of both families disprove this rumor, confirming his Shawnee ancestry. He participated in the Revolution as a British ally and in both of the Harmar and St. Clair defeats.

Although a brave man Blue Jacket lacked the tactical wisdom of Little Turtle and suffered from the vice of vanity. Blue Jacket expressed a “fondness” for fancy dress and drink that often offended those around him. He further proved the impetuous leader that the British needed at this time for keeping the Indians hostile toward the Americans.

Spurred on by the words of American renegade Simon Girty, the former American Loyalist and current British trader, Alexander McKee, the Indian leaders chose war. Misinterpreting the reinforcement of Fort Miamis as a sign of British support the assembled warriors eagerly sought combat.

On August 18th Wayne ordered the construction of Fort Deposit for leaving all of his excess baggage. While the troops built this fort, Wayne sent out his scouts for gathering the last intelligence before engaging the Indians. Upon their return they estimated about 1,100 Indians and about 100 “white men,” probably the Detroit militia. A heavy rain on August 19th delayed the Legion’s advance one day, allowing for more preparation. The soldiers marched at about eight o’clock on the morning of August 20th in battle formation on a hot, humid day.

Wayne organized his force into two wings, the right consisting of the 1st and 3rd Sub-Legions under Wilkinson. The left, consisting of the 2nd and 4th Sub-Legion under Lieutenant Colonel Hamtramck. Between the two wings Wayne placed his headquarters, artillery and reserve ammunition loaded on packhorses. An advance guard of scouts, under Major William Price, who previously scouted the terrain, marched well ahead for detecting ambush. Behind them came an advance guard of seventy-four regulars under Captain John Cooke.

Advancing with the Maumee River protecting the right flank, the command used it for guiding their route toward the Indians. Colonel Robert Todd’s brigade of mounted Kentuckians protected the left flank and Brigadier General Thomas Barbee’s Kentucky brigade served as rearguard. Across the river Captain Ephraim Kibbey’s mounted scouts from the settlement of Columbia, near Cincinnati, provided security.

The Indians awaited them in a natural fortification formed by trees felled by a past tornado, hence “Fallen Timbers.” Traditionally the Indians fasted before a battle in case they suffered a stomach wound. However the slow American advance caused hunger, and overcame about one-third of the Indians. Those who left the field in search of food journeyed a good distance from the battlefield, with many not returning. The hardcore among them remained in place and awaited the arrival of the hated Kentucky “long knives.”

Price’s men halted about one half-mile from the Indian position and prepared his men for battle. They took drinks of water, tightened their saddle cinches and stripped off excess clothing before resuming the advance. Two vedettes preceded the main body of scouts, Thomas Moore and William Steele, volunteered for this duty. They moved forward warily watching every bush and tree for sign of Indians, and soon found them.

The Indians opened fire from ambush felling both men from their horses, mortally wounded. Their comrades charged forward and engaged the Indians, finding Steele dead and rescued Moore. Under heavy fire Price ordered a withdrawal as the superior number of Indians attacked them.

Unfortunately they ran afoul of Cooke’s advance guard marching about four hundred yards behind the mounted scouts. Under orders from Wayne for firing on retreating militiamen, Cooke’s men mistakenly fired on the Kentuckians. This stopped the retreating Kentuckians, who now moved toward the river and reportedly left the field.

The Indians now engaged the small number of Cooke’s men, who valiantly stood their ground against the heavy odds. After firing three “good volleys” Cooke saw his situation and ordered a fighting withdrawal toward the main body. As Cooke’s men withdrew, Wayne deployed several companies of light infantry for screening the deployment of his battle line.

Wilkinson proceeded in making adjustments in his battle line when they intermingled with Hamtramck’s men. He encountered a company of dragoons under the command of the senior dragoon officer, Captain Robert MisCampbell. MisCampbell then reported that “Everything is confusion,” and asked Wilkinson for orders. Characteristic of Wilkinson, he declined, stating that his command did not include the dragoons and recommended that MisCampbell fall back. When one of Wilkinson’s subordinates requested that Wilkinson attack, he declined, citing an absence of orders from Wayne.

Wayne did issue orders that day, sending his staff in every direction for relaying even the most minute orders. The previous day’s rain and current humidity rendered the use of drums for signaling ineffective. He told his aide, Lieutenant William Henry Harrison, his standing order, “Charge the damned rascals with the bayonet.”

Believing the terrain near the river suited for mounted troops, Wayne ordered his dragoons into a flanking attack there. Unfortunately the bluffs along the river hindered a rapid advance by these troops and MisCampbell misunderstood the order. Instead of attacking with the full dragoon battalion, he used only his assigned company. When they struck the Indians, MisCampbell fell dead and the attack fell into confusion. Finally other dragoons appeared, as well as some Kentucky scouts, and eventually turned the Indian flank.

Wayne then ordered the unlimbering of his artillery, sixteen pieces, and opened fire on the Indians. Although the wooded terrain proved unsuitable for artillery, the psychological effect on the warriors justified their use.

The terrain in front of Wilkinson’s wing appeared more open, providing a better view of the enemy. While in front of Hamtramck’s wing the terrain appeared more wooded, making his assessment of the enemy more difficult. Subsequently, Wilkinson deployed his troops into a single battle line, possibly because of his better view. However, Hamtramck deployed his in the standard double battle line of the day, and in accordance with Wayne’s orders. This caused some confusion at the point where the two wings linked up, however it did not create insurmountable problems. Given the reduced numerical strength of the Legion’s companies, most estimates state that the deployment into line took about five minutes.

As the fire from the Indians increased, Wayne maneuvered troops for meeting each contingency. He ordered Scott’s Kentuckians on his left flank into the attack for turning the Indians’ right flank. The terrain proved too wooded and swampy for a mounted attack, so Scott dismounted them, using them as infantry. Here the Kentuckians engaged the Wyandots, who fought the Kentuckians almost fanatically.

Wayne adjusted his force by extending the left flank of the 2nd Sub-Legion until the American line stretched almost two and one-half miles. Satisfied, he ordered the advance with his men at “trail arms” for preventing their entanglement in the vegetation. Simply, the men advanced until within musket range, about fifty yards, from the Indians, fired a volley and charged with the bayonet.

Staff officers, seeing Wayne’s dash forward toward the battle, seized his horse’s reins, fearing for his safety. Despite the constant messages delivered by the staff, several officers did not receive the attack order. This often occurs during battle, the so-called “fog of war,” as the noise and adrenalin affect one’s abilities. However, here Wayne’s discipline and training standards proved their worth, as the officers advanced on their own initiative. Several officers quoted in Gaff’s book state that miraculously the entire line charged almost at once.

Now the Indians began a fighting withdrawal as the numbers of the Legion forced them from their cover. Groups of Indians stood their ground, many dying in place instead of retreating when overwhelmed. Others, seeing the superiority of the forces against them, fired once and then ran away and hid. By most accounts the stiffest resistance came from the Detroit militia, under the command of the American renegade Lieutenant Colonel William Caldwell. Most of the Indian resistance crumbled after about fifteen minutes and they ran toward Fort Miamis.

These Indians ran toward the shelter of the British fort with the soldiers of the Legion in hot pursuit. The fort’s commander, Major William Campbell of the 24th Regiment of Foot, lacking any specific orders, literally closed the gates. Heaping insult upon the defeat they just suffered, the demoralized Indians now realized the steadfastness of British support. Their British allies closed the gates and left them alone for facing the wrath of the victorious Americans.

With the Indians in full retreat and his men exhausted from the roughly about one hour battle, Wayne called a halt. The Legion remained on the newly won field for about two hours, resting and refitting. Details made a quick search for casualties and surgeons began the grisly process of attending the wounded. The Legion lost 26 killed and 87 wounded with none lost as prisoners of war. In celebration of the victory the soldiers received an extra ration of whisky and then prepared for further action.

Despite the defeat the Indians still possessed a viable force capable of a counterattack, although they lacked the spirit for it. However, Wayne and his men did not know this and took all the necessary precautions. He dispatched his scouts forward for gathering intelligence, not only of the Indians but Fort Miamis as well. Unfortunately, in his preparation for continuing his attack, Wayne neglected a thorough search for casualties. Later searches found that some of the wounded lay dying on the field, with one dying soon after his discovery on August 21st.

While this neglect may seem harsh, Wayne must consider the health and safety of the majority of his soldiers. He must focus on meeting the enemy, before they adequately reorganize, and hopefully limiting the number of future casualties. Searching for casualties today remains a responsibility of squad and platoon level leaders, and part of unit standard operating procedures (SOP). Higher headquarters does not specifically order it and depends on the initiative of subordinate leaders. While Wilkinson and other officers criticized Wayne for “ignoring his wounded,” why did they not remind him?

Regarding his concern for his sick and wounded soldiers, Wayne took great care of them throughout his tenure as commander. James Ripley Jacobs in his book, The Beginnings of the U.S. Army: 1783-1812, describes Wayne’s policies succinctly. He gave his surgeon general great latitude in ordering medical supplies and inoculating his soldiers for smallpox. Each company must provide one soldier as a “hospital steward,” the equivalent of today’s medic, for assisting the surgeons. He further ordered the hiring of “industrious humane and honest matrons” for serving as nurses.

After the battle Wayne correctly focused on engaging his enemies, and gathering intelligence on their capabilities. After his scouts returned Wayne left his wounded and surgeons with a guard force and advanced toward the British fort. He halted his force within one mile of the fort and in full view of the British garrison. The Legion constructed its fortified camp and settled in for the night, leaving a confrontation with the British for the next day.

During the night an American soldier, John Johnson, deserted and joined the British inside Fort Miamis. Johnson served with the Loyalist Queen’s Rangers during the Revolution and provided Campbell an accurate account of Wayne’s force and his intentions. He further revealed that half of Wayne’s force consisted of militia, due for discharge on October 10th.

Ironically a British drummer, John Bevan of the 24th Regiment, deserted the British and slipped into the American camp. He likewise gave Wayne an accurate report of the British forces inside the fort, and the treachery of the previously mentioned Newman. Bevan further confirmed that a company of British-armed Canadians fought alongside the Indians, an act of war. He told Wayne that the Indian army opposing him numbered “about two thousand men,” including the Canadians.

All day on August 21st the Legion rested and prepared for battle, with the men anxiously anticipating storming the fort. Wayne sent out Price’s battalion for scouting beyond Fort Miamis and searching for sign of the Indians. With the Indians gone Wayne took a small mounted party forward, including his aide, Harrison, and boldly rode toward the fort. Harrison stated that they rode within “pistol shot,” meaning a short distance, of the fort and studied the fort for thirty minutes.

An unnamed British officer stated that an impetuous young officer almost fired a loaded cannon on the Americans. His comrades stopped him and prevented this action, possibly saving Wayne’s life and definitely preventing war between the US and England.

The gates of Fort Miamis opened and a British officer appeared with a small detachment bearing a white flag of truce. He presented Wayne with a letter from Campbell inquiring of Wayne’s intentions regarding “His Majesty’s” fort. Wayne sent a rebuttal stating the Campbell illegally occupied the fort and demanded his withdrawal.

Wayne immediately sent for two days rations from Fort Deposit and developed his plans. He regarded Fort Miamis too strong for attack, particularly since he lacked heavy artillery for battering the walls. Furthermore, his army lacked the provisions necessary for a prolonged siege and the Indian army still remained at large. Wayne made several attempts at provoking a British attack, even riding within range himself again, but with no attack.

Meanwhile Wayne further demonstrated the impotence of the British at protecting the Indians by destroying their camp. With his troops running low on rations they confiscated all the food stored in the camp. They further destroyed those crops growing in the fields as well as all the buildings. This ensured a hard winter for the Indians remaining hostile, and a drain on British sources of supplies. They continued this destruction for the next two days without any interference from either the British or the demoralized Indians.

On August 23rd Wayne formally congratulated his Legion for “brilliant success in the Action of the 20th Instant.” Incapable of taking the British fort, Wayne and his Legion headed back for Fort Deposit and their provisions and baggage. On the return Wayne deployed his army in line for sweeping the previous battlefield, searching for any lost or abandoned equipment. No mention of searching for the missing wounded, but such a sweep surely found them.

As his army moved toward Fort Deposit Wayne and his men remained concerned about the still-absent Indian army. While the Battle of Fallen Timbers proved a milestone in American history, at the time most believed it merely a skirmish. The entire battle lasted less than two hours by most historical estimates with only about half of the Legion participating. The soldiers only found between thirty and forty dead enemies on the battlefield, hardly significant given the overall number of warriors. However, no records exist regarding those wounded evacuated by the Indians who later died from those wounds.

To be continued

BATTLE OF FALLEN TIMBERS CONFIRMS AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE-PART III

While Congress heard this testimony, Washington focused on the future regarding both the Army, relations with the Indians and foreign policy. Rebuilding the shattered army became his first priority, for without an army the nation remained defenseless. He sought, and Congress approved, a doubling of active duty strength, now set at 5,000. It initially contained five infantry regiments, one battalion of light dragoons (cavalry), one battalion of artillery and such medical and other forces as needed. Congress established through the Militia Act of 1792 federal authority over the organization and training of the state militias. It seems that throughout our nation’s history only military disasters force our leaders into providing adequate military forces.

First Washington must select a commander, a man capable of restoring confidence in the demoralized soldiers and recruiting new soldiers. He must further select a man capable of enforcing discipline and training standards on both officers and men, regulars and militia. This commander must further understand the complications of the Quartermaster Department and the logistical problems of frontier campaigns.

Washington looked at a list of sixteen generals from the American Revolution and consulted his Cabinet on the selection. Of the sixteen only three emerged as not too old, too ill of health or some other disqualification. His selection must also possess substantial military fame for passing the approval of Congress and stimulating recruitment. As a last choice, former Major General Anthony Wayne of Pennsylvania, became Washington’s new commander.

Wayne won the nickname of “Mad Anthony” for his exploits during the Revolution where he earned the reputation as an aggressive leader. He began his military career as the colonel of the Fourth Pennsylvania Battalion on January 3, 1776. Wayne took his command as reinforcement for the failing Canadian invasion where he proved his competence as a leader. In February, 1777 he received a promotion as brigadier general and served under Washington in some of the most famous battles of the war. At Valley Forge he earned a reputation at looking after the health of his troops and providing for their needs. He finished the war in the South under Major General Nathaniel Greene, including war against the British-allied Creek Indians.

Like so many famous generals, Wayne failed at much of his endeavors in civilian life, including a brief political career. His “fondness for the ladies” caused an estrangement from his wife and children, leaving him a lonely man. In truth, he needed the Army as much as it needed him and he eagerly accepted a commission as major general. He accepted with certain conditions, that he receive orders only from the President and Secretary of War. No congressional interference, no instructions from governors and no civilian delegations for undermining his authority.

Wayne soon found that he possessed no army except for the survivors of St. Clair’s debacle at faraway Fort Washington. Although Congress authorized four brigadier generals only three from a long list accepted: Wilkinson, on the frontier; Rufus Putnam of Massachusetts and Thomas Posey of Virginia. The situation grew worse when filling the ranks of subordinate officers because so many died under St. Clair. Further complications arose as these officers bickered over seniority, resigned over “insults” and even fought duels.

Recruiting from the mostly “civilized” East, the tales of Indian atrocities discouraged many from leaving their comfortable lifestyles. Nevertheless, officers spread out across the country offering a bounty of eight dollars for a three-year enlistment. These officers mostly recruited from their home states, where they enjoyed some reputation among the residents. Most companies unofficially became named after the commander and the state, instead of military designations. Despite the best efforts, many of these recruits came from the “lowest levels of society,” including criminals.

As these officers struggled at filling the ranks, Wayne remained in Philadelphia for preparing for his campaign. He gathered intelligence from surviving officers of St. Clair’s campaign and anyone else familiar with the frontier. Wayne further conducted extensive preparations regarding his quartermaster needs, appointing a competent former Continental Army officer, Colonel James O’Hara, as quartermaster general.

Wayne initially established his headquarters at newly constructed Fort Fayette, near Pittsburgh, finding only one company present for duty. From this poor beginning, troops gradually filtered in and Wayne began the arduous task of organizing and training his force. Once again, arms and equipment proved of poor quality, mostly leftovers from the Revolution. The uniforms and other clothing of the soldiers proved such poor quality that most civilians felt sorry for them.

The “dens of iniquity” of Pittsburgh proved a “training distraction” and a source of the Army’s many disciplinary problems. In November, 1792 Wayne moved his growing army down the Ohio River about twenty-five miles near the old Shawnee village of Logstown. Named Legionville after his army, now called “The Legion of the United States,” the soldiers first constructed winter quarters. Then Wayne focused on disciplining and training his force under a strenuous program that transformed it into a professional force. A man ahead of his time, Wayne developed some of the first “combined arms training” of the Army. He maneuvered all the elements, infantry, cavalry and artillery in joint maneuvers, including “mock battles” with blank cartridges.

Wayne further increased the marksmanship training of his men, including competition between the musket-armed infantry and the riflemen. He tried “modifying” the old French Charleville muskets and increasing their rate of fire, unfortunately the War Department disapproved. Then as now, bureaucratic “red tape” often hinders the commanders in the field.

The enforced standards of discipline and training did not create affection between the commander and his soldiers. Punishments fluctuated between execution, flogging and dishonorable discharge through as little as a verbal reprimand and public humiliation. Officers and men often called him “Old Tony,” “Old Horse” and “Mars” behind his back. Even worse, his second-in-command conspired against him and sowed dissension among the officers.

Wilkinson, far removed from the watchful eye of Wayne, wanted the supreme command for himself. Exercising an autonomous command at Fort Washington, Wilkinson, disregarded orders, communicated directly with Knox and criticized Wayne when possible. Because of Wilkinson’s efforts, the officers of the Legion formed into two hostile camps: those who supported Wayne and those for Wilkinson. Furthermore, by this time Wilkinson secretly served as an agent for Spain, receiving thousands of dollars in payment.

Wayne did not waste time while he awaited the arrival of more troops and provisions, he developed an ambitious plan. The US might lack an army, however it possessed a vast network of spies in both British and Spanish territory. Based on intelligence received, Wayne firmly believed that the US must eventually fight both England and Spain. At the time England proved the most significant threat, particularly for Wayne’s home state of Pennsylvania. He initially planned a two-pronged attack, not only against the Miami Confederacy, but forcing England’s hand regarding the illegally held American forts.

Wayne planned on leading the first wing, moving north from Legionville toward Presque Isle on Lake Erie, where the British held Fort Erie. This force operating on Lake Erie threatened not only the British forts, but also the arms and supplies for the Indians. Ascending the Maumee River, Wayne’s force threatened the hostile Indian villages from the rear, forcing them into dividing their forces.

Washington overruled this route for several reasons, and detailed them for Wayne in a long letter. If Wayne advanced, it threatened the neutrality of the Iroquois League, which might attack the Legion. Furthermore, the British possessed more naval vessels on Lake Erie than the entire US Navy. While the British may withdraw from Fort Erie without a fight, they might also reinforce from the other forts. The US still remained unprepared for another war with England, particularly if provoked by an American advance.

Wayne must rely on the plan for his proposed second wing, moving up the same road as St. Clair. Originally planned as under the command of Wilkinson, this plan called for an attack on Kekionga. He further planned on threatening Detroit, the main source of arms and provisions for the Indians.

History records the results of Wayne’s expedition; however an interesting “what if” scenario surfaces regarding the success of the original plan. Biographer and descendant of General Posey, John T. Posey, calls Wayne the “Patton of his day.” History records the many problems encountered by General George S. Patton that proved beyond his control. Of importance for this discussion, the supply problems that slowed Patton’s advance across Europe in 1944. Wayne’s quartermaster department already strained under the requirements before the Legion advanced into the field. Supplying two forces on the frontier might prove beyond the capabilities of the War Department, and hinder both operations.

Then we must address the leadership skills of the duplicitous Wilkinson, already on the Spanish payroll. In fairness, he achieved a good combat record during the Revolution, despite his dabbling in intrigue. Wilkinson did lead a small, though successful, raid deep into enemy territory, enhancing his reputation in Kentucky. He further performed a great service in holding together the remnants of St. Clair’s army. However, he performed these tasks for his personal aggrandizement, and he disliked serving as a subordinate. Did he possess the qualities for leading an expedition of this size and focusing on victory without considering his personal interests?

While the Americans rebuilt their army the Indians missed their best opportunity for turning back the tide of settlement. Following Little Turtle’s victory a council of several tribes broke up without making any decision regarding future operations. The same bad weather that hampered St. Clair’s advance also hampered the fall harvest for most of the tribes. Furthermore, they suffered from the destruction of homes and crops by the two Kentucky militia expeditions.

The Miami abandoned their villages and moved around the various British trading posts, making them more dependent. Tribes from the upper Great Lakes region returned home for the winter and promised further aid in the spring. The Wabash and Illinois tribes signed peace treaties with the Americans, taking most of their warriors out of the fight. Of further importance, the still-powerful Iroquois remained neutral, with some supporting the Americans, jealous of the Miami power.