Many of you may be familiar with Osprey Publishing, which produces hundreds of titles related to military history on a variety of subjects. Those interested in the forts of the British colonies and New France will enjoy two titles that Osprey released a few years ago. Forts were important to the history of the colonial frontier, as some of the pivotal battles of the wars that occurred in North America between Britain and France were fought for control over fortifications (ex. Forts Duquesne, Carillon, and the fortress of Louisbourg). Therefore, understanding them and how they were constructed is important to understanding the broader competition for empire in North America.

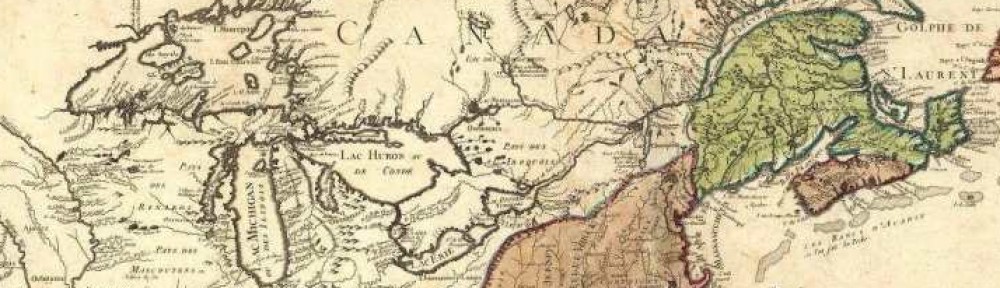

In 2010, Osprey released The Forts of New France: The Great Lakes, the Plains and the Gulf Coast 1600–1763 by Rene Chartrand. The book is a wonderful introduction to the various levels of fortifications and change over time of them across France’s far-flung colonial empire in North America. Several would be fought over during the series of wars between France and Britain (King William’s War, Queen Anne’s War, King George’s War, and the French and Indian War).

The book is beautifully illustrated, as is customary for Osprey products, with several plates devoted to different forts in New France. The book follows a chronological and geographical flow, examining the forts of each region of New France (Gulf Coast, Plains, and Great Lakes region) from the earliest period of French colonial activity to the conclusion of the French and Indian War, when France was expelled and the territory transferred to British control.

The garrison sizes were discussed, as most forts in the regions were smaller affairs, served by only a couple dozen troops. In addition to establishing French claim over the area, the forts served as centers of trade and establishments of relations with Native Americans. Many of the early forts were established specifically to facilitate trade with Native American groups, especially those in the Great Lakes area (the Pays d’en Haut). Most forts were simple wooden construction and relatively small, but some grew into very large stone fortifications by the eighteenth century.

The forts covered allowed France to maintain its authority over such a vast swath of North America and make its claims over areas. They also served as scenes for the struggle for empire between Britain and France, and with Native Americans in North America. One fort that I was delighted to see included was Fort de Chartres in southern Illinois. I have visited this restored post several times, as it is only a couple hours from my hometown. The book discussed to two distinct fortifications at the site, first wooden, later replaced by stone, both under constant threat from the Mississippi River.

Like the French, the English (later British), Dutch, and Swedes established forts in their colonies to serve as places to claim territory, establish trade with Native Americans, and protect their imperial frontier from French and Native incursion. In The Forts of Colonial North America: British, Dutch and Swedish colonies (2011), Chartrand examined the history of fortifications built by the English, Dutch, and Swedes during the 17th century and the conquest of the latter by the English. Later, these sites became the backbone of British control over its North American colonies and the front line of defense when war with France raged. Like the French, these forts also started as smaller, simple wood-constructed stockades, with some growing into larger wooden fortifications, or taking on stone facades.

This book provides a wonderful general introduction to early colonial history along the American coast and traces the history inland, as Britain begins to establish inland forts. Several forts are illustrated in beautiful color plates that attempt to show readers what they may have looked like in their day. One fort that is featured is Fort William Henry, site of a major siege during the French and Indian War that was later novelized and dramatized in James Fenimore Cooper’s Last of the Mohicans and its film adaptations.

Rene Chartrand was an excellent choice to write these works, as his background is fitting for writing such works for a broad audience seeking a general informative overview. He served as curator for over three decades for Canada’s National Historic Sites before venturing into freelance writing. This allows him to write the works for the casual reader that is seeking knowledge on the broad subject as opposed to a deep academic analysis.

Both books provide wonderful information about the subjects they cover, including detailed maps, chronological tables of key events, as well as glossaries of terms related to the subjects, allowing readers who do not have the background to better appreciate the subject covered. Though geared towards general readers and non-academic audiences, these two books are great for those seeking to get an introduction to the forts of colonial America and some basic factual information surrounding them. They serve as a springboard for diving into other literature on the subjects of fortifications, New France, British America, relations with Native Americans, colonial military history, and a bit of engineering.

Well-researched and illustrated, these two books are worth having on your shelf if remotely interested in colonial era fortifications. While they focus on the sites of empire, Osprey also suggests other related titles that deal with the troops of the various imperial powers fighting for control of North America. At less than $15, these books are a great deal to begin building a library on colonial history and can be enjoyed by readers both young and old, though I would say a good minimum age for these works would be around 12-14 given the subject matter and terms used.

If a fan of Osprey books, or just a casual interested person looking for something different, certainly give these two works a try.

Chartrand, Rene. The Forts of New France: The Great Lakes, the Plains and the Gulf Coast, 1600-1763. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2010. Illustrations, Maps, Photographs, Index. 64 pp. $10.42.

Chartrand, Rene. The Forts of New France: The Great Lakes, the Plains and the Gulf Coast, 1600-1763. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2010. Illustrations, Maps, Photographs, Index. 64 pp. $10.42.