Reviewed for On Point: The Journal of Army History

Cubbison, Douglas R. The British Defeat of the French in Pennsylvania, 1758: A Military History of the Forbes Campaign Against Fort Duquesne. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2010. ISBN 978-0-7864-4739-8. 10 photos, appendices, notes, bibliography, index. 251pp. $49.95.

Cubbison, Douglas R. The British Defeat of the French in Pennsylvania, 1758: A Military History of the Forbes Campaign Against Fort Duquesne. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2010. ISBN 978-0-7864-4739-8. 10 photos, appendices, notes, bibliography, index. 251pp. $49.95.

Military historian Douglas Cubbison explores a turning point in the French and Indian War (1754-1763) with great detail. The capture of Fort Duquesne was a major victory for the British during the war and redeemed the disaster that befell Edward Braddock’s expedition against the Fort in 1755. Cubbison makes the bold claim that the campaign against Duquesne led by Brigadier General John Forbes was “among the most important in American history.”(1) There is certainly credibility to this argument, as the capture of the Fort turned the tide of the war in Britain’s favor, which led to final victory. The claim has merit within the context of British victory in the war being the catalyst of event that led to the Revolutionary War. The importance of the campaign is primarily within the confines of the French and Indian War itself.

Cubbison’s motivation for creating this study of the Forbes Campaign lay in his observation that no dedicated scholarly study was produced for the 250th anniversary of the campaign in 2008.(1) He stressed that his study was different from most historical treatments of events, as he did not delve into social history, and focused on only British and colonial sources.

Each chapter covers specific subjects on the campaign. The first chapter discussed the life of John Forbes and his appointment to command of the expedition. Subsequent chapters deal with organization of the forces, logistics, geography, supply, setbacks, and eventual British victory in the campaign. In addition, appendices provide information about items brought along the campaign, including ordinance and trade goods for Native Americans.

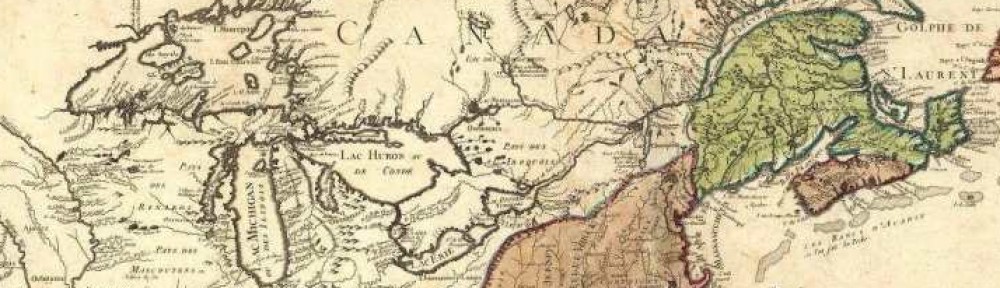

Several positives stand out in this work. First is the incredible detail. If readers want to know statistical knowledge of the campaign, Cubbison will satisfy such curiosities, as he provides many segments of primary sources, as well as the appendices noted above that contain itemized listings of military material and other relevant statistics, including casualties and hunting results. Second, is the inclusion of a couple of hand-drawn maps from the campaign, which illustrate the difficulties that Forbes and his force had to overcome in their advance against Fort Duquesne. Finally, the documentation is thorough, with many notes and an extensive bibliography.

Despite the positives of the book, there are some areas of concern. One is the focus on only a select group of sources, mainly British. While Cubbison defends this in his introduction, the choice to focus on a select group of material limits the scope of his examination and the potential audience. Further, while it is stressed that the study is not a social history, which resounds with some readers, incorporating some social history would have added to the richness of the story of the Forbes campaign. A second issue was the long block quotations of primary sources, as while such sources are essential to a historical work, such long quotes, as opposed to paraphrasing, can cause readers to lose track of Cubbison’s history. Finally, the lack of maps is a small, but important problem, as while this book is intended for those with background knowledge, a map, or maps, would better aid in understanding the campaign, as well as expand the potential audience.

Overall, Cubbison produced a traditional military history on an important campaign in American history. While this book is geared to a rather focused audience, scholars and readers of military history will find it a useful source, as Cubbison provides amazing statistics and coverage of the many facets of an eighteenth century campaign in America. While there are some issues with the book, this study of the Forbes campaign is long overdue and opens the door to future scholarly study on the subject.